Joseph Ebnöter

Biography

Ebnöther’s place of birth is Oberriet in the canton of St. Gallen. A copy of the family coat of arms can be found in the canton’s state archives. From 1952 to 1955, he completed an apprenticeship as a sign painter and painter with museum curator and restorer Eugen Lutz in Altstätten. Various ornaments and paintings on facades, gables and wooden shutters of old half-timbered buildings in his hometown of Altstätten can be found from this period and from his time as a journeyman.

From 1956 to 1965, he attended courses at the School of Applied Arts in St. Gallen, including seminars on form and colour with Jürg Schoop, Diogo Graf and Fredi Kobelt. Between 1959 and 1962, Ebnöther frequently interrupted his training with stays in Paris to attend courses at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the École des Beaux-Arts for figurative drawing lessons.

In Paris, his first visit to an art exhibition led him to the works of Nicolas de Staël. At another exhibition, Marc Chagall shook hands with him and one of his fellow students, passing many other guests. In later years, his circle of friends included the DADA artist Cornelia Forster and one of the founders of the Erker-Presse, Franz Larese, brother of the writer Dino Larese. Franz Larese put Ebnöther in touch with the lithographic printing workshop Speicher, which produced numerous colour lithographs for him over the following decades.

Ebnöther began working as a freelance artist in 1957, and in 1969 he had his first major solo exhibition at the Ida Niggli Gallery in St. Gallen, which exhibited his works at the first Art Basel. Another early patron, the Iris Wazzau Gallery in Davos, also presented his works at Art Basel and at international art fairs, bringing him to the attention of a global art audience.

Between 1956 and 1980, he undertook numerous study trips within Europe and to Africa. These trips resulted in numerous representational and abstract paintings with motifs from these regions.

In 1979, the Kantonsschule Trogen presented the film Der Maler Josef Ebnöther und seine Umgebung (The Painter Josef Ebnöther and his Environment), and in 1990, Bruno Zaugg from St. Gallen made a documentary about him in the form of a video. Four more films about the artist and his oeuvre were made in the following years until 2023. In 1992 and 1993, he was responsible for running seminars at the Kunstraum Dornbirn in Austria. In southern Switzerland, in Ticino, Ebnöther had three working stays at the villa of the Fondazione Richard e Uli Seewald, an artists’ residence in Ronco sopra Ascona, until 2017.

Ebnöther enjoys exhibiting his work alongside sculptures by artists such as Silvio Mattioli, Robert Schad, Herbert Albrecht and Armin Göhringer. ‘Ebnöther thinks not only in colours, but also in light and architecture.’ He has created reliefs in wood and steel for public spaces. In 1998, he produced a series of mixed media works on handmade French paper, which was also used by the American sculptor Richard Serra. Ebnöther’s son Josef (born 1956) is also a sculptor, known and referred to by the name Pli Ebnöther.

Since 1999, he has been collaborating with Swiss poet Elsbeth Maag on various art projects. In 2006, works by Joseph Beuys and Josef Ebnöther were shown in a joint exhibition in Zurich. In 2019, the artist designed the anniversary badge for the Röllelibutzen carnival in his hometown.

Ebnöther lives and works in Altstätten, high up in the district of Lüchingen, overlooking the St. Gallen Rhine Valley. His house has been listed as a historic building, and he has filled the hillside garden with numerous sculptures by international sculptors.

Beginnings

Ebnöther’s first publicly known oil painting, Italia, which he painted in 1956 at the age of 19, was described by museum director Roland Scotti as an ‘incunabulum’.[8] This beach scene contains everything ‘[…] that would occupy the artist for the next almost fifty years: the elements of water, earth, air, perhaps even the fire in the stormy sea; […].’ The painting is figurative, but the first signs of pictorial reduction are noticeable. Museum director Dieter Ronte put it this way:

“He sweated out his Cubism; he packaged his deconstructivism, his Jackson Pollack, experienced God as abstraction, and then found his own specific formal vocabulary. […] It took a lot of effort. Stumbling blocks such as […] Ferdinand Hodler, […] Nicolas de Staël […] and Clifford Still had to be overcome.”

During this phase of his life, he created paintings that show echoes of colour field painting, such as Composition, 1964, oil on canvas. He was initially influenced by the works of Mark Rothko, Amedeo Modigliani and Nicolas de Staël.

From around 1965 onwards, his paintings became more ‘formally reduced and abstracted into colour-intensive surfaces.’ In his early work and later, he often painted his oil paintings on jute and mixed sand into his paints. He frequently worked with painting knives, palette knives and squeegees. He also produced his first colour lithographs and gouaches.

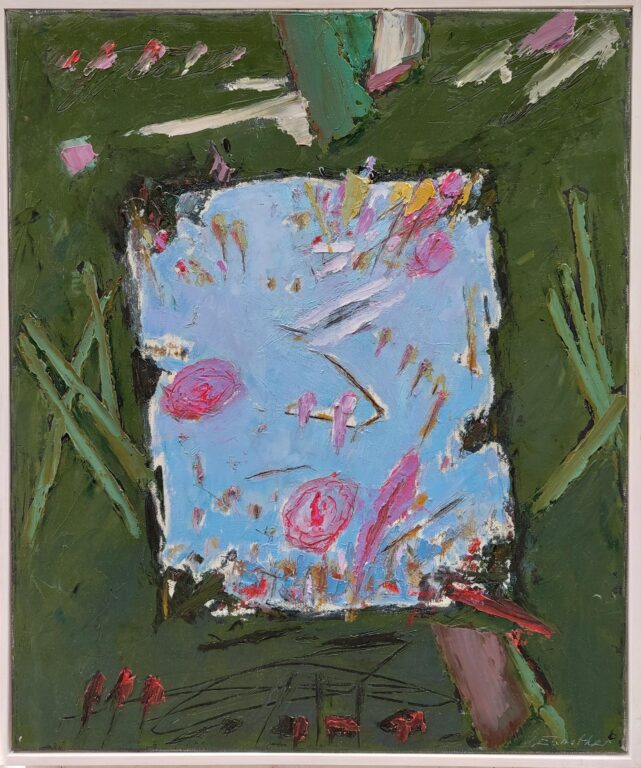

After building his house in 1971, he was inspired by the view over the opening valley of the Rhine. This resulted in numerous paintings entitled Rheintal (Rhine Valley), some with references to the respective season. “Ebnöther loves autumn and the beginning of winter. This time of year means peace and introspection to him; the season has something apocalyptic about it, filled with the hope of a new beginning.” Abstract works with titles such as Weg (Way) or Herbst (Autumn) are titles that recur throughout the decades.

Commissioned works and sacred images

The artist received his first private commissions in 1959. Since 1967, he has also received public and church commissions. These include oil paintings, large wood and steel reliefs, mosaic pictures, tapestries and stained glass windows.

Among the commissioned works in 2019/20 were artistic works related to the Ecumenical Bible Week in Germany. Prior to this, Ebnöther had designed and realised all the stained glass windows for the Church of St. Joseph in Kempen near Düsseldorf between 1992 and 1993. The stained glass windows cover a total area of 220 m². They were manufactured by the glass manufacturer Derix. During this art project, he got to know and appreciate the sculptor Ulrich Rückriem, who had a lasting influence on his many subsequent table paintings. The table motif as a ‘[…] wide-ranging symbol of communication, security and sacrifice characterises the paintings of an entire decade (Landscape Table, 1992; Table, 1996). To this day, religious motifs and their subjective reinterpretation play an important role in Ebnöther’s work (wall design for the Lüchingen cemetery, 2001; […]).’ The abstract Good Friday oil paintings from 1985 to the present day fall into this context, even though Ebnöther does not paint dogmatic church images.

In his home town, in the Catholic chapel in Riet, the motif of the path can also be found in one of his paintings: Maria Wegbegleiterin (Mary, companion on the path). This is one of his ten abstract votive paintings, painted for this place of pilgrimage, the Riet Chapel. In the canton of Solothurn, in the Protestant Reformed Church in Dornach, the stained-glass windows he designed are entitled Der Weg zum Licht (The path to light).

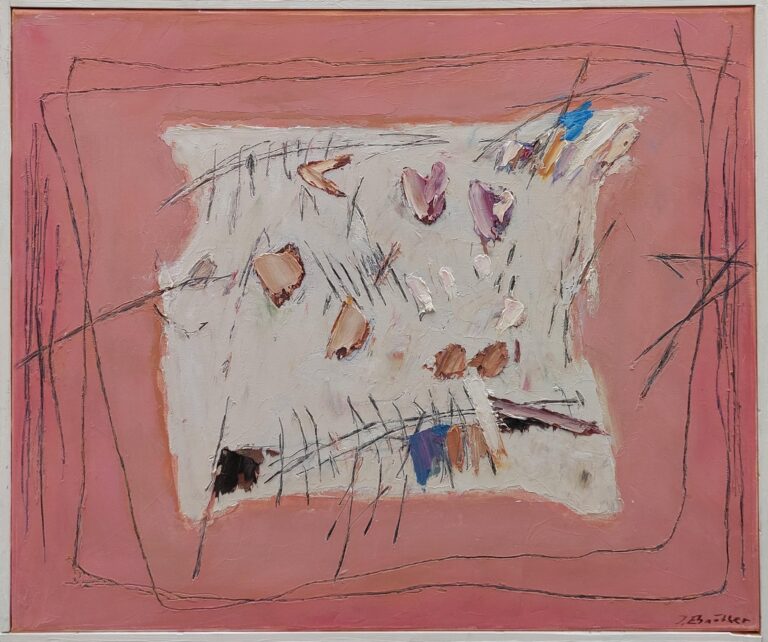

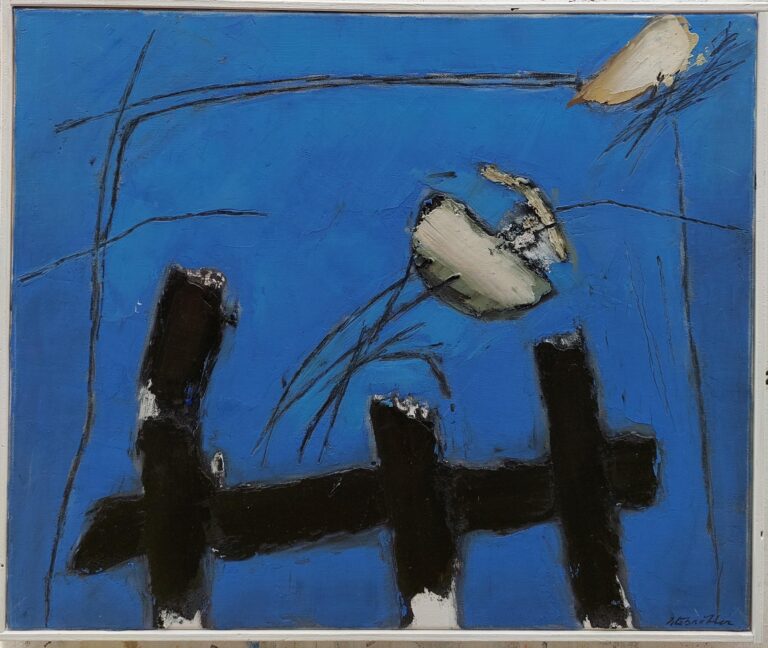

Pictures with dissolved forms and gestural symbols

From around the mid-1970s and early 1980s, Ebnöther processed his observations of the landscape, sensory impressions, emotions, thoughts, everyday situations, human encounters and objects from nature into pictures whose creative process he could no longer explain.

The abstract images with radically dissolved forms, perspectives, colour compositions and gestural symbols are dependent on impulses and moods, ‘the message of the image is constantly changing – and remains open even at the end, when Ebnöther dabs on the last moments of colour.’

‘His working method is captivating with its powerful style. First, surfaces are built up in many layers of colour, often with a deep, translucent effect […].’ Then – especially towards the end of his painting process – Ebnöther often works on the still-fresh paint on the canvas of a picture, partially with violent, spontaneous and unconscious gestures. To do this, he usually leaves relief-like traces and marks on the canvas with the tip of his painting knife or with blunt pencils. This is why it is also referred to as grattage. Because of his unconscious gestural painting in parts of his pictures, he once ironically and incorrectly described himself as an ‘informal painter’. The picture surface is often divided by lines or harsh colour contrasts. The symbolism of these pictorial elements seems like secret messages. These are sometimes hinted at by the respective picture title.

The titles of the paintings are usually decided upon retrospectively and often refer back to the original, fleeting conception of the image. He struggles with his titles because he wants viewers to come up with their own thoughts and feel free. ‘Ebnöther creates “open works of art” in the sense of Umberto Eco, […]’

Late work

‘The images in his late work show […] a brightening of colours and a refinement of the line-dot structure.’ His late work, which has been clearly recognisable since 2017, is not yet complete.

“Currently, the artist is correcting the picture ground in an even more differentiated and delicate manner than in earlier years. […] Whereas in the past, rough, plastic compositions of layers of paint placed next to and, above all, on top of each other determined the working process, Ebnöther now tends to use a squeegee and spatula in a dynamic, dancing manner across the picture ground when developing his images. […] Over time, Ebnöther’s forms have become increasingly organic and seem to arrange themselves fluidly on canvases that have also become lighter overall.”

Reception of Josef Ebnöther’s work

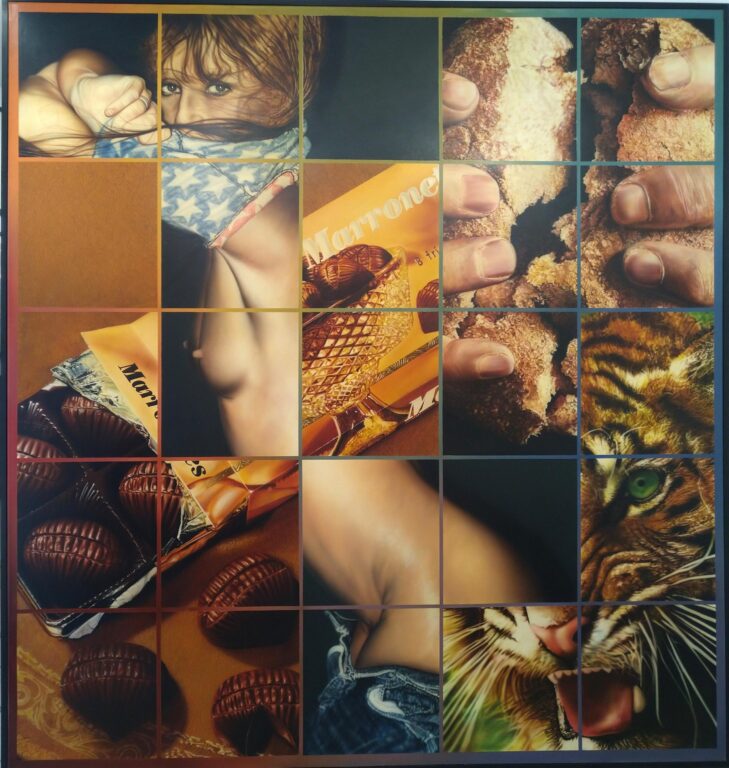

Ebnöther’s themes could be summarised as follows: ‘the violence of war, the protection of Mary, the happiness of freedom, light, colour and love, anger at the power of consumerism and a constant balancing of human existence with nature.’

‘Without being derivative, his paintings tie in with the tradition of abstract expressionism.’ According to the blurb for another publication, Ebnöther’s ‘painterly explorations […] ingeniously build on informal and abstract expressionism and consistently take these international styles in a different, individual direction.’ The blurb also states that he is ‘an anarchic artistic antipode to the Zurich School of Concrete Art, which rigorously dominates Swiss art with its strict formal geometric pictorial logic.’ Winfried Nussbaummüller, head of the culture department in the Austrian state of Vorarlberg and former curator of the Kunsthaus Bregenz, sees echoes of ‘[…] a poetic, lyrical expressionism’ in Ebnöther’s work.

Ebnöther, however, always refused to be pigeonholed by art historians and mocked such attempts. He followed his own artistic path and took his own position without proclaiming it loudly. In the decades of his artistic career, he never followed the fashion trends in painting.

‘His painting seeks the original and the elementary and refers to the unconscious, to spiritual forces. When characterising his art, the term “mystical” springs to mind.’ Museum director Gert Ammann puts it this way: ‘Ebnöther’s oil paintings are meditative images.’

Josef Ebnöther’s painting ‘[…] transcends boundaries – both geographical and spiritual.’ For him, painting is an act of freedom.

CV

Exhibitions

- HOFFNUNG / HOPE – GMT Galerie Marc Triebold 2026

- January 23, 2026 - May 24, 2026

- GMT Galerie Marc Triebold, Baselstrasse 88, CH-4125 Riehen / Basel

-

Siegfried Anzinger, Alexander Archipenko, Georg Baselitz, Joseph Beuys, Georges Braque, Elisabetta Brodaska, Jürgen Brodwolf, Bruno Ceccobelli, Marc Chagall, Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, ab 1982 Marqués de Dalí de Púbol, Martin Disler, Joseph Ebnöter, Hans Erni, Max Ernst, Emile-Othon Friesz, Alberto Giacometti, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Utagawa (Ando) Hiroshige, Katsushika Hokusai, Karl Horst Hödicke, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Livia und Michael Kubach und Kropp, Anna & Wolfgang Kubach-Wilmsen, Wilhelm Kuhnert, Richard Lindner, Fernand Léger, August Macke, Franz Marc, Henri Matisse, Mario Merz, Helmut Middendorf, Joan Miró, Benno Oertli, A.R. Penck, Peter Phillips, Pablo Picasso, James Rosenquist, Richard Seewald, Hans Thuar, Hans van Reekum, Wolf Vostell, Andy Warhol, Raymond Emile Waydelich, Jan Wiegers, Bernd Zimmer