August Macke

Works

Biography

CV

LIFE AND WORK

AUGUST MACKE 1887–1914

August Macke is one of the most important pioneering artists of the early 20th century. He tirelessly experiments with forms and colours in his search for a new artistic language. The well-read and open-minded young man sought an artistic form of expression that would do justice to the revolutionary achievements in the fields of science and the humanities. In doing so, Macke acted independently of bourgeois conventions and the prevailing conservative view of art. French modernism in particular became his most important source of inspiration.

I. Balance on the edge of the abyss

In 1914, his last year of creative work, the 27-year-old August Macke painted a picture of a tightrope walker. The impression of a variety show on the market square in Thun (Switzerland) becomes a parable of the modern artist. Experiences and imaginings merge into a new reality. The artist acts in a downright reckless manner, balancing far above the heads of the spectators at the height of the gables of the houses above the market square. The figure of the tightrope walker symbolises the fragile social situation of the modern artist, who moves away from official paths and conventions. Thus, the tightrope walker also represents August Macke himself. Today, Macke is one of the most popular artists of the first half of the 20th century. He is considered a cheerful, accessible expressionist. Paintings from his important periods of work fetch prices of over 2 million euros at auctions. During his lifetime, however, there was little sign of this enthusiasm. Contemporary viewers imagined something completely different when they thought of art, and the unusual use of colour was met with great incomprehension. With his new painting style, Macke was at constant risk of losing his livelihood – just like the tightrope walker in his painting. Against the backdrop of the German imperial era and its strict social norms, Macke’s life and artistic development proved to be a consistent but often arduous path. At the turn of the century, many European artists found themselves in the same situation. Artists and jugglers served as metaphors not only in art but also in literature for the ambivalent predicament between brilliant flights of fancy and existential danger.

II. Education, artistic beginnings

On 3 January 1887, August Robert Ludwig Macke was born in the small town of Meschede in the province of Westphalia. His two sisters, Auguste and Ottilie, were many years older than him. His father was a self-employed building contractor and his mother came from a farm. Macke grew up in Cologne, then in Bonn. His childhood was overshadowed by the economic difficulties of his father’s company. Even as a schoolboy, Macke had only drawing on his mind and played a key role in designing the stage sets for school performances. Against his father’s wishes, he dropped out of school at the age of 17 to become an artist and began studying at the renowned Düsseldorf Art Academy. His professors considered the young student to be exceptionally talented. However, the conservative educational concept did not correspond to Macke’s ideas at all. As it had been for centuries, painting historical pictures depicting significant events from history or the present was still considered the highest goal of academic training. The same applied to the technical perfection of drawing in order to create as accurate a representation of reality as possible. All of this had little in common with the innovations of his own time. Macke sought other inspiration for his art: in books, in the art magazines that were increasingly appearing on the market, in exhibitions and in nature itself. In his early paintings, nature conveys mood and meaning, symbolising his very personal feelings. The shape of a tree, the movement of the waves in the water, the harmony between man and nature, and the restrained colouring underline the romantic mood and the proximity to symbolism.

III. French Impressionism as a source of inspiration – trips to Paris

Macke gains more exciting impressions at the Düsseldorf School of Arts and Crafts, where he takes evening classes. Reform ideas had already found their way into this training centre for future artisans. Macke also gained practical experience at the Düsseldorf Schauspielhaus. The newly founded theatre became a reform stage through its lively performances of modern plays. As a set and costume designer, Macke played a decisive role in their implementation. ‘I would create moods through curtains and colours alone, without imitating nature,’ he said, expressing his revolutionary ideas. He felt that the path he had taken so far was a dead end. He gave up his academy training and also turned down the permanent position as stage designer that was offered to him. This required a great deal of courage and a healthy dose of self-confidence. He wanted to be free from external constraints and develop his own artistic language, even if this meant taking a huge risk, not only financially. When he saw photographs of paintings by French Impressionists in 1907, they opened up a new world for him – even though they were only black-and-white prints. It is the focus on the reality of life and the completely new painting style that fascinates him about these pictures. And so he has nothing more urgent to do than to travel directly to Paris, the Mecca of modern art. Like so many of his young contemporaries who are disappointed by the academy, he allows the originals of the paintings in the art galleries of Durand-Ruel, Vollard and Bernheim-Jeune to work their magic on him. The Café du Dôme even became a meeting place for all those seeking inspiration, for artists, gallery owners and collectors. Macke learned to see in a new way and turned to Impressionist light painting. On two further trips to Paris in 1908 and 1909, he consolidated his engagement with modernism.

Ah, Paris is surely the most beautiful city in the world. […] I am growing ever fonder of the Impressionists.

August Macke, 1907, from Paris

I am currently more convinced than ever of the excellence of the French school.

August Macke, 1910

IV. Colourful imagery with Fauvist echoes

Impressionism and Japonism, which Macke is also enthusiastic about, liberate him from tradition. Nevertheless, he senses that this is not the end point of his development as a painter. After completing a year of military service, a new phase of life and a new artistic phase begin. In 1909, he married his childhood friend Elisabeth Gerhardt. Due to her pregnancy before marriage – a scandal at the time – the young couple withdrew from Bonn and even considered settling in Paris. However, the rents were too high, so they finally chose Tegernsee near Munich. Elisabeth was his muse, model and, as Macke himself wrote, his ‘second self’. His surroundings and everyday household objects, arranged in the living room due to the lack of a studio, also find their way into his pictorial worlds. The colours radiate across the surface and begin to take on a life of their own. The viewer is confronted with a decorative overall tone, with colourful outlines and unusual image details. This reveals the influence of the French Fauvists, the modern exhibition community around Henri Matisse in Paris, whose works fascinated Macke in Munich in February 1910. But another exhibition also had an impact: the ‘Exhibition of Masterpieces of Mohammedan Art’, for which Henri Matisse travelled from Paris to Munich especially. At the beginning of the 20th century, modern artists were inspired by evidence of foreign cultures as well as by a conception of painting that was far removed from the European tradition. Around 1910, the term ‘Expressionism’ was coined for the new style in order to conceptually summarise the contrast between this painting style and Impressionism.

The offer of his own studio, designed entirely according to his ideas, prompted August Macke to return from Tegernsee to his old home in Bonn at the end of 1910, together with his wife Elisabeth and their young son Walter. His mother-in-law provided them with a small late-classical style house on the edge of the factory grounds of her company, Gerhardt, whose attic was converted into a spacious studio according to Macke’s plans. Until Macke was called up for military service on 2 August 1914, his new home was the hub of his diverse art-political activities. Artist friends such as Robert Delaunay, Max Ernst and many others came and went here. Many of his most famous paintings were created in the bright attic studio, and during a visit by Franz Marc in 1912, the two painted a large picture of paradise on a four-metre-high wall. The adjoining large garden was a playground for the children and an important motif in his paintings.

V. National and international networks – The artistic friendship between August Macke and Robert Delaunay

The modern styles influenced by the French avant-garde, the artists, their gallery owners and collectors not only aroused displeasure in the German Wilhelmine Empire, but also made them suspect of pandering to France, the hereditary and arch enemy. The press labelled Expressionist artists such as August Macke and their works ‘crazy’, “insane” or ‘degenerate’. Excluded from official exhibition opportunities, they had to take the marketing of their works into their own hands and founded independent associations. Between 1911 and 1913, Macke became an important art-political driving force and gifted networker in the Rhineland, Munich and Berlin. Rhetorically skilled, extroverted and with an engaging personality, he made contacts, organised exhibitions and gave lectures. ‘He is extremely good at advertising and is skilled in his presentation,’ said his Russian colleague Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) appreciatively. New groups of buyers had to be tapped, but above all, it was important to awaken an understanding of modern art. To this end, German modern artists networked among themselves, but also beyond national borders. Close contacts were established not only with Russia, Switzerland and Scandinavia, but above all with France and Paris. Macke befriended Robert Delaunay, whom he visited in his Paris studio in 1912 together with Franz Marc. In January 1913, Delaunay and Guillaume Apollinaire stopped off at Macke’s place in Bonn. From then on, the two artists exchanged ideas on art and very private matters and worked together on the international intertwining of modernism. Delaunay was repeatedly invited to exhibit his modern paintings at avant-garde art exhibitions organised by August Macke and his artist friends, at the travelling exhibition of the Blue Rider (1911/12) and at the legendary First German Autumn Salon in Berlin (1913). Berlin patron Bernhard Koehler, uncle of Macke’s wife and one of the few collectors of ‘living art,’ provided financial support to Macke and his friends for their exhibition and book projects. He was also Macke’s most avid buyer, acquiring two paintings by Robert Delaunay for his collection.

A work of art must be well-conceived nature, a well-chosen selection, a mirror of feelings.

August Macke around 1912

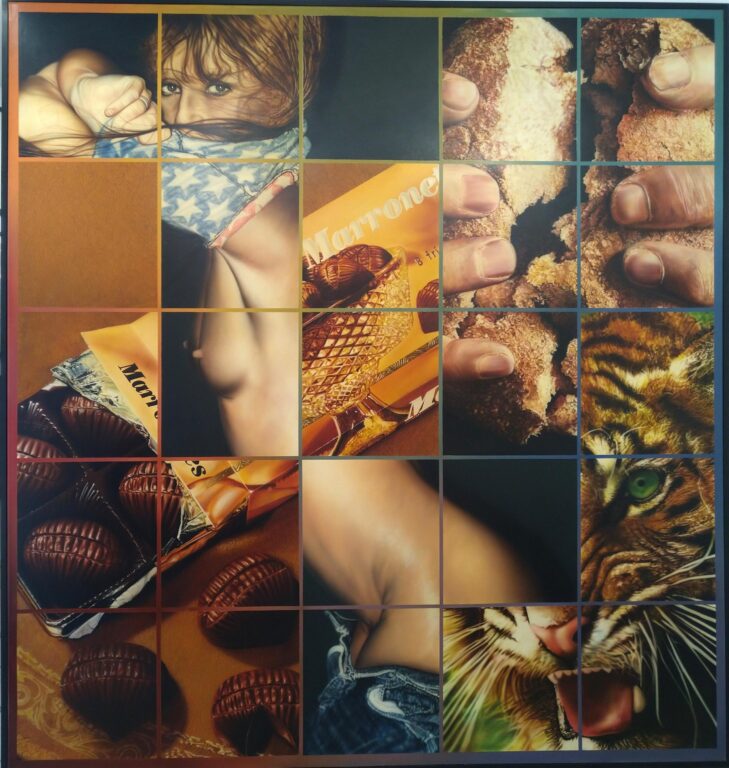

VI. Cubist and futurist stylistic devices open up new possibilities

Industrialisation and technical inventions are changing the appearance of cities and the everyday lives of their inhabitants. Around 1911, Macke is looking for new painterly means to illustrate this. He finds inspiration once again in the current trends in French and Italian painting, in the vanguard of the latest, the avant-garde: in the Cubists and Futurists. On a trip to Paris with his artist friend Franz Marc, he sees their works, for example at Vollard’s, but also in various small gallery exhibitions in Germany, where works by Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso and the Futurists are on display. Macke uses these stylistic devices in his drawings and paintings: breaking down objects into their individual parts, reducing them to lines, repeating rhythmic forms, and using small, chopped-up, geometric snippets. This enabled him to illustrate movement and at the same time express the fast-paced, noisy, pulsating hustle and bustle and technical progress – as an almost abstract pattern or collapsing onto his figures. Numerous solo exhibitions and participation in exhibitions in 1912 and 1913 testify to his recognition by the open-minded art scene. ‘Incidentally, painting always brings in so much that it would be better to be lazy,’ Macke complains about the lack of sales. It takes perseverance to withstand hostility time and again and to pursue an artistic path that goes against the spirit of the times, especially since Macke has to contribute to the upkeep of his family with two young sons. The regular monthly support from his wife’s wealthy family is only enough to cover the basics. But he confidently states: ‘I am no longer interested in the opinions of others about my paintings.’

VII. Arts and crafts as part of lifestyle

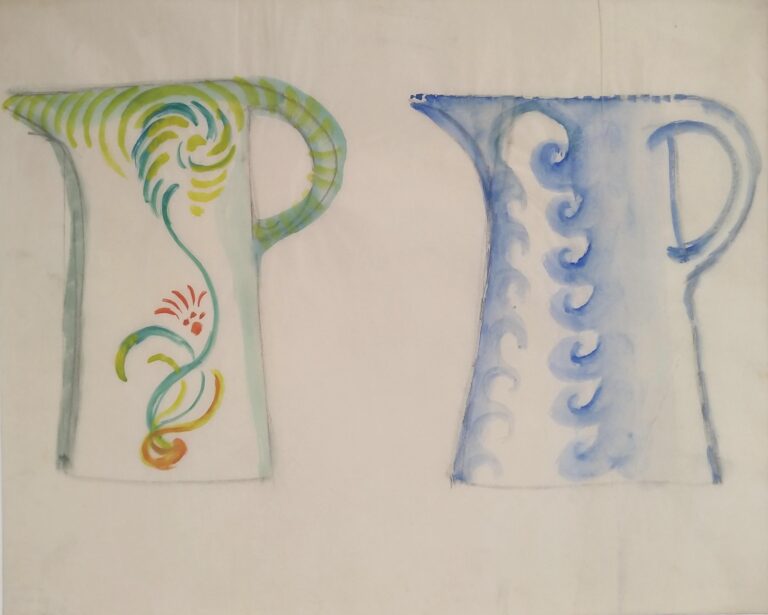

For Macke, art and handcrafted everyday objects are a ‘form of life’ and belong together. It is important to the Expressionists to design their living environment as a total work of art according to their own modern ideas. In his bright studio in Bonn with its large skylight, he works not only at the easel, but also at the workbench. He paints porcelain and designs embroidery, which he often sketches directly onto the fabric. Macke designed his first embroidery patterns in 1905, out of dissatisfaction with traditional motifs. His wife Elisabeth, her mother and grandmother carry out the designs. On the occasion of a lecture by Macke, Elisabeth even wears a reform dress based on his designs. Macke also designed door fittings, sideboard supports and jewellery, and made furniture, cushions and carpets for private use. But in the commercial sector, too, modern designs were to replace traditional patterns that were no longer in keeping with the times. The most important concern is to restore Germany’s reputation, which suffered in the 19th century due to the inferior quality and antiquated appearance of its products. Inspired by the reform movement of the German Werkbund, Macke designs functional and modern everyday designs for tableware in 1912, which are exported. ‘I am now working with porcelain,’ he wrote to his patron in Berlin. He made a name for himself as a designer and in 1913 was commissioned to completely redesign the dining rooms of a tea salon in Cologne. Colourful sketches and numerous designs convey an idea of Macke’s concept, which was never realised due to the outbreak of the First World War.

The work of art is a parable of nature, not a representation. […] it is the thought, the independent thought of man, a song of the beauty of things.

August Macke 1913

VIII. Earthly Paradise

Macke regarded life with his wife and two sons as happiness, and art and life as ‘rejoicing in nature’. This positive attitude to life found its own unique artistic expression, particularly during his years in Bonn from 1911 to 1913. In his pictorial worlds, he created varied and multifaceted representations of an earthly paradise. His works reveal themselves to be a vision of a harmonious world and, as a ‘song of beauty’ (Macke), are at the same time a counter-concept to his era, which was characterised by technical innovations and industrialisation. While the great world exhibitions of the 19th century in Paris and London located the South Seas or the Orient as distant places of longing, Macke transferred his earthly paradise to the here and now of the real world. Everything turbulent, destructive and negative is blocked out. The garden appears as a place of leisure and comfort, as a real idyll. Humans and animals are also depicted as a harmonious, primal unity in Macke’s pictures of zoological gardens, as are his lovers and family scenes. The harmonious coexistence of married couples, as it appears in Macke’s pictures, the mutual care and respect for one another, were not always a matter of course in bourgeois circles at the time. To symbolise the couple’s deep connection, he introduces a new formal language borrowed from the Orient with the crouching figures. In intimate, everyday scenes, Macke stages the world of children, who appear natural and uninhibited, absorbed in their play. The relationship between parents and children is redefined here in line with progressive education, which no longer regards children as decorative accessories.

IX. Artistic synthesis

In order to be able to devote himself entirely to art again without the distractions of art politics, Macke leaves the bustling Rhineland with his wife and two young sons in October 1913. He settled in Oberhofen, Switzerland, directly on Lake Thun, for eight months. The apartment in Haus Rosengarten was idyllically located directly on the water, opposite the impressive panorama of the Swiss mountains. Inspired by the ‘sun-drenched window panes’ (Macke) in Robert Delaunay’s paintings, he developed his own unique artistic vision here shortly before the outbreak of the First World War. Nature as an experienced phenomenon remained his starting point, but he now changed and combined different motifs. By assembling the works from individual forms like a painted collage, he created new visual worlds according to his own ideas. They appear realistic, but are fictional. Both in terms of motif and in the prismatic decomposition of forms and colours, the influence of his friend Robert Delaunay can be clearly seen in Macke’s shop window pictures. However, Macke translates the Frenchman’s abstractions into contemplative, cheerful visual worlds. Since muted, dreary shades of grey tend to dominate facades and cityscapes in the real world, the colourfulness of Macke’s pictures can be read as a metaphor. Macke’s famous trip to Tunis in April 1914, which he undertook with his friends Paul Klee and Louis Moilliet, lasted fourteen days. The southern light, the exotic motifs: the artists felt as if they were in a fairy tale. ‘It’s going like the devil, and I’m enjoying my work as I’ve never known before,’ he reports. He brings home an endless number of drawings, watercolours and photographs, which he later uses in his studio in Bonn.

Finding these space-creating energies of colour, instead of being satisfied with a dead chiaroscuro, is our most beautiful goal.

August Macke 1913

War is of a nameless sadness.

August Macke 1913

X. The First World War

After his return to Bonn in the summer of 1914, Macke falls into a creative frenzy. He produces his most famous paintings. The artist sees his task as helping to shape modernity through a new aesthetic: children against the backdrop of an industrial harbour landscape or a modern iron lattice tower next to a venerable Gothic cathedral. He sees less the negative consequences of the new, the isolation and alienation, and more the opportunities it opens up. When Austria declared war on Serbia at the end of July 1914 following the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne, Macke sensed the approaching end of an era and the imminent interruption of his creative work. There was no way around immediate conscription after the mobilisation of the German Empire on 2 August 1914 – Macke was a trained reservist and sergeant. At first, there was a certain enthusiasm – despite the close friendships and artistic connections with French and Russian artist colleagues. There was hope that the war would sweep away everything old and finally make room for the new. But after the first major battle, Macke was completely disillusioned. Euphoria gave way to despair over ‘the horror.’ Only seven weeks after the war began, Macke fell on 26 September 1914 in Perthes-lès-Hurles in Champagne. A sombre-looking, unfinished painting remained on his easel in his studio. After Macke’s death, Elisabeth is left behind with two young sons. Not only has she lost her great love, but she now also has to bear the burden of caring for her young family and managing his artistic legacy. In a heart-rending obituary, Macke’s friend Franz Marc lamented the immeasurable loss to German art: ‘With his death, one of the most beautiful and bold curves in our German artistic development comes to an abrupt end; none of us is capable of continuing it.’ Two years later, he too was killed in action.

XI. Aftermath

August Macke was greatly admired by his fellow modern artists. But only a few collectors have become buyers. The sole exception is Bernhard Koehler, who owns over 50 works by Macke alone. Not a single museum purchased any of Macke’s paintings during his lifetime. The artist gave away many of his paintings as gifts to collectors or in return for organising an exhibition. It was only after the First World War that Expressionist painting began to be appreciated. The previously misunderstood artists were appointed as professors at the finally reformed art academies. Macke’s paintings also found their way into museum collections. But only for a short time, because as part of the ‘Degenerate Art’ campaign in 1937/1938 and the travelling exhibition of the same name, these works were confiscated by the National Socialists from public collections. As a source of foreign currency, the Nazis sold the artworks they classified as ‘degenerate’ at auctions in Switzerland or through specially commissioned art dealers. After the Second World War, museums were forced to completely rebuild their collections of Expressionist art. Many paintings are still missing today; every now and then, some of these works appear on the art market. A process of re-evaluation and appreciation began in the 1990s in particular. Today, Macke exhibitions are real blockbusters. The paintings from his last creative years before the First World War, the ‘typical Mackes’, which have found their way into many households and the collective memory as prints on mugs and in calendars sold in museum shops, now fetch prices on the art market that exceed a million and are hardly affordable for publicly funded museums.

Text: Ina Ewers

Exhibitions

- HOFFNUNG / HOPE – GMT Galerie Marc Triebold 2026

- January 23, 2026 - May 24, 2026

- GMT Galerie Marc Triebold, Baselstrasse 88, CH-4125 Riehen / Basel

-

Siegfried Anzinger, Alexander Archipenko, Georg Baselitz, Joseph Beuys, Georges Braque, Elisabetta Brodaska, Jürgen Brodwolf, Bruno Ceccobelli, Marc Chagall, Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, ab 1982 Marqués de Dalí de Púbol, Martin Disler, Joseph Ebnöter, Hans Erni, Max Ernst, Emile-Othon Friesz, Alberto Giacometti, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Utagawa (Ando) Hiroshige, Katsushika Hokusai, Karl Horst Hödicke, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Livia und Michael Kubach und Kropp, Anna & Wolfgang Kubach-Wilmsen, Wilhelm Kuhnert, Richard Lindner, Fernand Léger, August Macke, Franz Marc, Henri Matisse, Mario Merz, Helmut Middendorf, Joan Miró, Benno Oertli, A.R. Penck, Peter Phillips, Pablo Picasso, James Rosenquist, Richard Seewald, Hans Thuar, Hans van Reekum, Wolf Vostell, Andy Warhol, Raymond Emile Waydelich, Jan Wiegers, Bernd Zimmer

- August Macke and Hans Thuar

- June 14, 2025 - September 30, 2025

- GMT Galerie Marc Triebold, Baselstrasse 88, CH-4125 Riehen / Basel

-

Elisabetta Brodaska, Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, ab 1982 Marqués de Dalí de Púbol, Keisan Eisen, Genki (Komai Ki), George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Hermann Hesse, Utagawa (Ando) Hiroshige, Katsushika Hokusai, Imao Keinen, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, August Macke, Emil Nolde, Gerhard Richter, Shunshosai Hokucho Shunchosai, Hans Thuar, Kunichiko Toyohara, Andy Warhol, Raymond Emile Waydelich