Peter Phillips, 21.05.1939, Birmingham, UK – 23.06.2025, Birmingham, UK

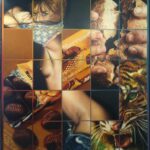

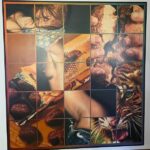

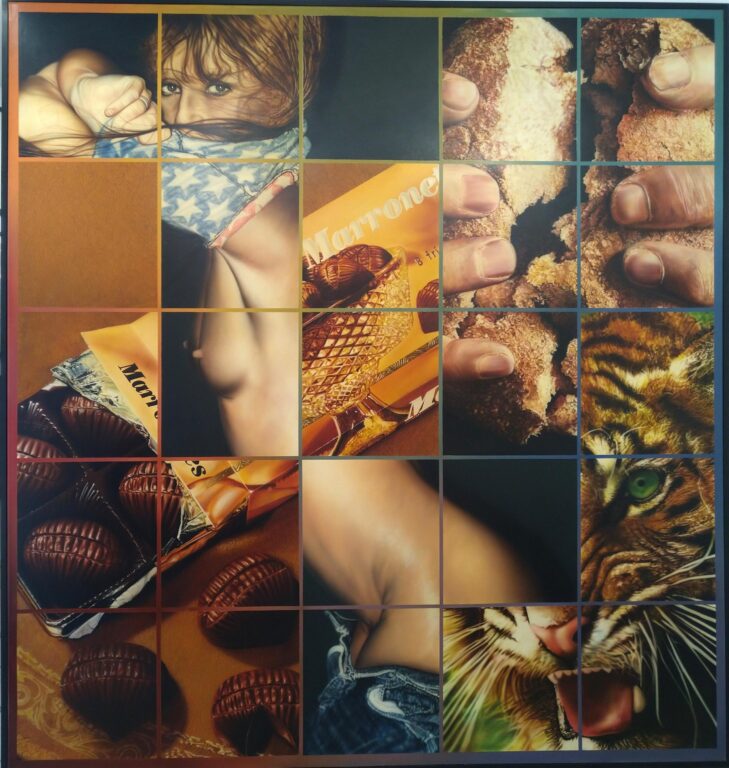

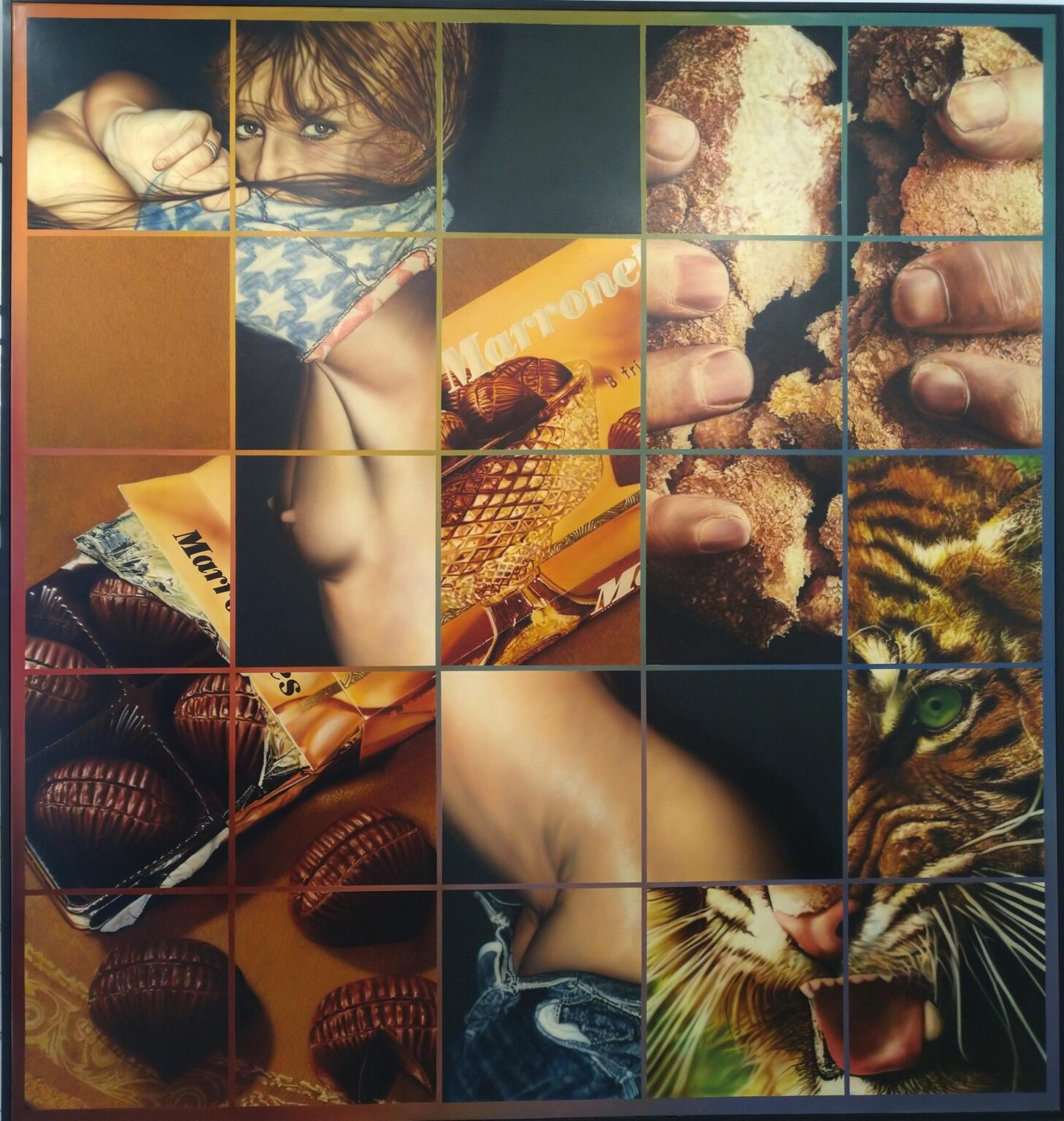

Mosaikbild 5 x 5, Supergirl, 1975,

Oil on canvas

Signed and dated on the verso of the canvas as well as on the stretcher and titled on the stretcher

200 x 200 x 3 cm,

Provenance: Waddington Galleries, London (1976); bought there in Art Basel, private collection Othmar Triebold, Switzerland; Private collection Pierre Marti, Switzerland; Heirs of the former.

Since 1975, however, Peter Phillips has been prepared to ‘manufacture’ his

own ‘found’ material, choosing the actual objects he wants to use and having them

photographed professionally under carefully controlled conditions with a large format

camera. This gives him not only greater flexibility in the choice of image and of its

particular configurations, but also a much finer degree of detail. Whether the image

be of a lobster, a parrot or a snake, however, every motif has been translated into two

dimensions before the painting is begun. Nothing is painted directly from life. No

fundamental change, in other words, has taken place in Phillips’s manner of working.

The first paintings based on this kind of high-definition photograph, Mosaikbild

5x 5/Supergirl! 1975 and Mosaikbild/Displacements 1976, were occasioned by personal considerations. “My wife Claude said to me once, “You’re. always painting women, why don’t you ever paint me?” So being a nice guy I said, “Okay, why not?” She looks okay, she looks as good as all the pin-up girls. I took her to a photographer’s studio and photographed her with a professional pin-up photographer, I got a load of photographs, then I chose again in the same way the ones that appealed to me, and put them in the painting. So the process, in fact, is not different. It was just a question of a personal thing with Claude, but there’s no great difference. Instead of a found object, she became, in a sense, an archetype for all of these things. They’re images for all images.

Marco Livingstone, Peter Phillips,

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, 1982:

The Pop paintings produced by Peter Phillips during the 1960s, large in scale, brilliant

in colour and polished in finish, today seem to encapsulate that era, and they

have lost none of their formal or emotive power over the years. Bold and aggressive inconception, even the earliest paintings, executed when the artist was barely in his

twenties as a student at the Royal College of Art. startle today with their directness of

impact.

Ata time when many artists were flirting with modern technology, Phillips immersed

himself wholly and without apology in the machine aesthetic. His range of images —

whether of automobiles, machine parts, predatory animals, pin-ups or scientific diagrams

~ was drawn exclusively from readily-available printed sources, mass-produced,

cheap and familiar to anyone living in this society. Phillips’s techniques and compositional

methods, likewise, were appropriated from commercial art and from industry,

not just in his use of the airbrush for an anonymous perfection of finish but in his

habit of recycling images from one painting to another as if they were the interchangeable

parts of a modern machine produced by assembly-line methods.

Over the past two years a radical change has taken place in the appearance of

Phillips’s paintings. The ‘Pop’ label sits uneasily with them. Big enough for the artist

to ‘move around in’ but less over- powering in scale than the canvases of a decade ago,

these are colour fields, painted with conventional brushes rather than with an airbrush,

against which are disposed isolated fragments of dimly recognizable but enigmatic

images such as animal skins. The dazzling colours of Phillips’s previous work

have given way, for the time being at least, to more subtle and sombre hues, The surface,

though still tightly controlled, no longer aspires to a machine-like perfection

and anonymity, but instead bears traces of the artist’s hand in building up the paint

to the required density.

The new paintings may look very different from the earlier work, but in fundamental

terms of attitude and approach nothing has changed. The collage principle is still

at work in the intuitive Juxtapositions of images from magazines and similar readymade

material. Technique continues to be a major preoccupation, with surprising mixtures

of materials normally thought to be incompatible and with three-dimensional

additions which extend the pictorial illusions into real space.

The new paintings provide eloquent proof of the lateral, rather than linear, thinking

which lies at the root of Phillips’s work. The outward form of the paintings has been

drastically rephrased by a change in the nature of the imagery and in the tools and materials

employed, but the content, if defined in terms of operating principles, remains

basically unaltered.

“There’s a series of many different overlapping preoccupations that keep emerging and

disappearing, and then might re-emerge under some other disguise concedes Phillips.

‘In one sense |’m constantly reaffirming everything I’ve done, but at the same time

constantly destroying, ending that and starting a new thing. But for me that’s the only

way it carries on being interesting.”

This attitude of wilful contradiction is the source of a number of conflicts both conscious

and unconscious, within Phillips’s work. From the beginning he has brought

together elements generally considered to be mutually exclusive, not just in the way

of technique but in terms of stylistic affiliation. The machine aesthetic merges with

colour held painting, Pop crosses over into Conceptual Art as advertising imagery

gives way to the artist’s own market research, and geometric abstraction is injected

with the intuitive juxtapositions of images characteristic of Surrealism. It is not a question

of deliberately seeking to combine opposites, but rather of adapting to his own

ends whatever he finds of interest.

Phillips has drawn from a great range of twentieth century are; Cubist and Dadaist

collage and photomontage, Surrealism, Léger and Purism, Kandinsky, Abstract

Expressionism, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg have all left their mark. He has

also studied pre- Renaissance painting and, more recently, has explored the techniques

of Dutch still life painters such as Jan Davidse de Heem (1606-84). In Phillips’s view,

however, it would be an unnecessary conceit or intrusion to make direct reference to

the work of other artists in his own paintings. Instead his preference is for ordinary

images of the kind one comes across every day, painted with recourse to tools and materials

— household gloss paint. car paint. photographs and the airbrush — familiar

from outside of the realm of fine art. Often choosing deliberately vulgar imagery,

Phillips nevertheless commands an extreme refinement of technique, even though his

method of painting may have been adapted from an equally unrespectable source in

commercial art,

Phillips maintains that anything can be material for a picture, yet he has demonstrated

on many occasions a preference for a particular range of obsessive images.

Magazines, books, and decals have provided a convenient range of images already

processed into two dimensions, the result being that there has been a preponderance

of advertising and mass media imagery: games, motorcycles, cars, machinery, pin-ups.

‘To view the paintings purely as a materialistic revelling in consumer products, however,

would be to ignore the emotional dimension provided by the juxtaposition of

images, bold colours and geometric elements, just as seeing the images exclusively in

terms of their two dimensions would be to miss the consistent involvement with illusions

and with complex spatial systems.

There is no doubt that, until recently, Phillips’s paintings have been aggressively direct.

and that much of their impact has emanated from the positively-stated images,

rendered as precisely as possible so as to provide an immediate point of recognition

and contact with the viewer. In terms of meaning, however, the paintings are disconcertingly enigmatic and open-ended. Rather than direct the viewer’s attention towards a thematic resolution, Phillips expects the viewer to take responsibility for making sense of it for himself.

‘A person who looks at a painting should be able to create himself, he should have the

freedom to interpret, This is why a painting for me must be complicated, with a lot

of different references, handlings of paint, points of view and illusionistic changes.

You can read it in a million ways. It just depends on how interested the particular person

is, the mistake is to look at it in a particular way and say “That’s that.” It’s not. |

would prefer chat it remain in chat state of tension. | would prefer that there is a game

which can constantly be played with the painting which is never resolved. You can’t

win, you can’t lose. It’s better that way, because then the painting is self-generative.

Each individual can interpret it in his own way.“

Phillips is not cumulating mystery for its own sake when he refuses to pin down the

meaning of his paintings, nor is he taking the easy way out when he says that a variety

of interpretations are possible but that no one reading is necessarily the ‘correct”

one. His urge to involve the viewer as a collaborator and active participant rules out

the possibility of imposing specific meanings, These visual games are an invitation to

share in the artist’s emotional life and experience of the world, with an emphasis on

the sharing. Since no manual activity is involved, the game is ready to be played at any

time; all that is needed to set it into motion are one’s own emotions and intellect.

Games are meant to be fun, and there certainly is a great deal of pleasure afforded by

Phillips’s work in terms of colour, form, surface and imagery. lt soon becomes clear.

however, chat it is not all light-hearted and easy-going. Even the fun-fair, beneath its

surface of glitter and excitement, has its monsters, its distorting mirrors, its confusion

of noise and movement. There is a sense of unease, too, in Phillips’s paintings — sometimes

obliquely stated in images of sexual frustration or impending violence — reaching

at times an almost hysterical pitch in the frenzied cluster of sharply-defined images

against stridently-coloured backgrounds.

It might be objected that I have already overstepped the bounds of neutrality by reading

particular emotional values into the paintings. The issue, however, is precisely that

the paintings cannot be appreciated as coolly-calculated celebrations of popular culture

or merely as pleasing or dynamic formal arrangements. Some measure of interpretation

is essential on the part of every viewer in order to release the emotional and

mental potential of each picture, but it does not matter whether one interpretation accords

with another, for there is no single ‘solution, and therefore no winner and no

loser. Assaulted and numbed by the constant How of images every day of our lives, is

it not cause enough for celebration that paintings can still spur us to feel and to think?

The sense of menace which infiltrates this celebration is, perhaps, only the other side

of the same coin: a despair on the part of the artist that the people he wants to reach

may not be interested in art in any case. One is enticed towards the paintings by various

means: largeness of scale. brilliance of colour, familiarity of imagery, beauty of

surface and virtuosity of technique. Having been seduced into looking at the painting,

the problem of meaning is then thrown back to us, leading us, paradoxically, to

a state of confusion within the context of a very assertive statement. Once more we

are returned to the state of tension and to the contradictions which form the very substance

of Phillips’s work.

“There is no such thing as nonsense,’ maintains Phillips, who regards painting as an

unconscious activity, ‘One “dreams” into a painting, Not in the sense of Dali, but this

inexplicable feeling that one has, and a sudden, spur of the moment decision, are very

important. | really dislike a painting when it is logical. It loses its spontaneity, and this

is the only way | can retain any spontaneity, when | have a very logical way of working.

Conceiving of his paintings as visual equivalents for emotions, it is essential to Phillips

that decisions be made impulsively but that they be executed very methodically. ‘It’s

very related to Surrealist painting, the early beginnings of dissimilar elements together.

This fascinates me. You put two things together, and it becomes something else. If

you put them together right, it generates a totally new experience that can be very

powerful.’

A perpetual need to surprise himself thus underlies the formulation of each painting

as well as Phillips’s development as a whole. ‘Te becomes boring when you know what

you’re doing. That’s why, even though is always the same, there are abrupt stylistic

changes in my work,’

Arbitrariness, in Phillips’s view, is not to be mocked or feared, bur accepted as an essential

part of the creative process. In the discussion of the artist’s development which

follows, some of these intuitive leaps will be singled out for examination in the hope

that they may provide a few clues as to the sort of intuitive responses expected in return

from the sympathetic spectator.

Binge 1960, painted by Phillips some months after his arrival at the Royal College of

Art in the autumn of 1959, is one of his earliest surviving paintings and the first evidence

of the direction his work was to take over the following decade. Basically

heraldic in its imagery and apparently spontaneous in execution, it nevertheless represents

a synthesis of the conflicting artistic interests and experiences which had preoccupied

him since his early teenage years. The artist’s initial technical training, his

study of pre-Renaissance painting, and his encounter with Abstract Expressionism

and with the work of Jasper Johns all play their part.

Born in 1939, Phillips entered art school at the age of thirteen, spending two years

(1953-55) at the Moseley Road Secondary School of Art in Birmingham, a school of

applied arts where he was taught a number of disciplines including painting and decorating,

sign-writing, heraldry, silversmithing, graphic design, architectural illustration

and technical draughtsmanship. Phillips acknowledges that these craft skills,

learned at an impressionable age, have all left their mark. as has the general emphasis

on technical discipline and on perception,

‘l remember certain techniques that impressed me at the time, and certain ways of

thinking, attitudes, who knows, they have some sort of subconscious effect on you

later.’

Significant, too, was the fact that Art History was not even mentioned, and that at

first Phillips had no specific intentions of becoming a painter. Romantic visions of the

artist’s role or great ambitions to remake the Old Masters thus were, and have remained,

completely alien concepts to him, In their place was a more purely physical

pleasure in the visual stimuli in the world around him, and a desire to be of his own

time.

Only alter his move to the Birmingham College of Arts and Crafts in 1955, in the second

year of his Intermediate Course, did Phillips decide to become a painter, It was

during this period that he exhibited his first paintings, Social Realist ‘political paintings’

with titles such as The Dispute and Early Shift. “Birmingham is a factory town,

and in those days a very working class orientated area. | just used to go out and draw

factories and strikers. | did quite a lot of those sort of street things with rather grey

people, and painted the billboards and all chat sort of thing.’ Phillips was soon to reject

this particular form of figuration and especially the clement of overt social comment,

but the habit of taking his subjects from the immediate environment is one

which has stayed with him.

While still at Birmingham, Phillips became interested in fourteenth and fifteenth

century Italian painting, his curiosity whetted in part of the Pre-Raphaelite collection

at the City Art Gallery. An opportunity to study at first hand the work of painters

such as Cimabue, Giotto, Uccello and Bellini came with the travelling scholarship

awarded to him by the College of Arts and Crafts on his departure in the summer of

1959. His journey took him first to Paris and then to Florence, Venice and other

Italian cities; he bypassed Rome, presumably because its treasures of High

Renaissance and Baroque painting held less fascination for him.

‘] did particularly like early Italian painting, pre-Renaissance Sienese and Florentine

painting, where they split up the surface of the painting. It wasn’t an illusionistic

space. it wasn’t this hole in the wall | was fascinated by the way they would divide up

a panel, They would paint a figure and then they would have five or six little scenes

going on, and to me that was very beautiful, and still is, as is much manuscript illustration,

| like it very much, because it deals with another sort of space. Asa rule | tend

not to like the High Renaissances o much; the paint | like, but this illusionistic space

as a totality never interested me so much.

“The early painters weren’t interested in representing a scene, but as far as | can recollect,

when an artist was painting the Virgin, that thing was the Virgin. These little

extra things were stories that were symbolically complementing the Virgin of whatever

it was. It was very interesting, because what they did was the object, whereas later

on they were representing something, Even though it was very complex again in its

metaphor, we don’t particularly understand it, because unless you’re a scholar we have

no symbolic education any more. It possibly worked on other levels then, but for us

it’s just an illusionistic semi-narrative illustration, with its only interest in the various

types of paint and compositional organization. But this type of unity didn’t interest

me enough.’

Prior to his departure for ltaly, Phillips had become acquainted for the first time with

Abstract Expressionism at the Tate Gallery exhibition of The New American Painting

held in February-March 1959. It was a particular revelation for an artist who recalls

asking as late as 1956, ‘Do Americans actually paint?’ He remembers being impressed

most by Willem de Kooning and Clyfford Stull, and to a lesser degree by Philip

Guston and James Brooks, though Barnett Newman he found ‘too radical.’

Contact with Abstract Expressionism provided Phillips with the impetus to move onto

a larger scale when he took up his place at the Royal College of Art in 1959. Among

his fellow students, only Derek Boshier was working on a similar scale, although other

artists revealed related interests: David Hockney at the time was working in an idiom

inspired by Alan Davie, Allen Jones was studying the work of pioneers of abstraction

such as Wassily Kandinsky and Robert Delaunay, and R.B. Kitaj — an

American himself, and seven years older — was adapting de Kooning and Robert

Rauschenberg to personal ends. On the whole the other students were painting still-

lifes and portraits in a rather traditional idiom, using a small scale and rather muddy

colour.

Outside the Royal College, ‘Abstract Expressionism was all the rage’, as Phillips recalls.

Abstract painters of a slightly older generation, such as Bernard Cohen Robyn

Denny and John Hoyland (then finishing his studies at the Royal Academy Schools),

were responding in their own way to the boldness and large scale of American painting.

Phillips knew Hoyland slightly at the time but had little contact with the others;

any formal similarities between Phillips’s games-board paintings of 1960 onwards and

the work of these hard-edge painters can be traced to common interests rather than

to any direct influence from the older British painters. A more direct factor was the

friendly spirit of competition between Phillips and the other young painters with

whom he was sharing a flat at $8 Holland Road, Kensington, all of them students at

the Royal Academy.

‘At College you were learning “advanced figure painting” or whatever — just student

exercises — and at home one was trying to make one’s own cultural contribution. The

College was still geared to figure painting, but it was never explained why, or what

one should get out of it. It was just a discipline that one had to do. So obviously one

revolted against that when one was home and did exactly the opposite. | can’t imagine

that anyone knew what he was doing. | certainly didn’t. One was just trying to

make paintings that looked like other people’s paintings. | remember Michael Upton

always had sort of Rauschenbergs lying around, and he was trying to knock off Larry

Rivers type paintings and doing it pretty well. David Willetts, who also lived in the

flat, was doing Jackson Pollock type paintings. [t was a whole mixture, The small

room was full of these people, it was very exciting in a way, and everybody was trying

to do their thing. De Kooning was the biggest influence at that time because he was

at least more Europeanized than the other Americans, so you had perhaps a little

more contact with it. Everybody was trying to imitate de Kooning. You had your

book of de Kooning open and you were painting your pictures.’

The only one of Phillips’s paintings in this vein which survives, Big Orange, bears closer

comparison with the work of other British artists such as Gillian Ayres than with

the paintings of the Americans. Thinly painted in orange and green, with much of the

white canvas showing through, 1 consists of curvilinear forms suggestive of plant

growth or flowers, loosely brushed with veils of colour.

Phillips’s efforts to paint in this manner were short-lived. A turning-point, he recalls,

was having one of his paintings, Afar Tenderness, laughed ac by the art critic Lawrence

Alloway during the setting up of the Young Contemporaries exhibition in March

1960, Phillips had met Alloway while still a student at Birmingham and respected his

opinion, knowing of his position in the art world though unaware of his previous involvement

with the Independent Group at the Institute of Contemporary Art.

Alloway’s spontaneous reaction came as a salutary shock, and Phillips decided to rid

his work of eclecticism and of characteristics that were foreign to his own natural abilities,

“I realized before that | wasn’t an expressionistic type of artist in this gestural

sense. So I did exactly the opposite and tried to do that which [ already had some familiarity

with, and that was controlled painting.”

Binge 1960 marks Phillips’s return to the principles of ‘controlled’ painting which he

had learned in Birmingham, at the same time displaying a tentative move into the

funfair imagery which he was soon to make his stock-in-trade. The colour remains

muted, orange, red and yellow vying with black, brown and white; the artist’s touch

is still of central importance in the thin but sensuously-brushed surface; and there

continue to be echoes of de Kooning’s paintings of the 19405 in the ambiguous ovoid

forms in the centre.

What is new here is the heraldic simplicity of the imagery in the top row — a Fleur-de-lis.

a target. and a club of clover shape — and its compartmentalization within rigidly-

defined areas. This method of encasing subsidiary images as a means of establishing

a formal relationship with the central visual event is one of a series of personal responses to the characteristics of the early Italian altarpieces which Phillips had been

studying. The tall vertical format itself can be related to this source, as can the organization

around a central axis, with purposeful deviations from absolute symmetry.

Different spatial systems co-exist, the suggestions of a shallow interior space in the

central area counteracted by the flat and frontal boxed-in images above. Consistency

of meaning’ in a representational sense is disregarded — with enigmatic images placed

arbitrarily against coloured backgrounds and a blandly-stated row of colour samples

– since abrupt changes can be neutralized by the relative homogeneity of surface.

Edges are sharply-defined, the outlines drawn in pencil and then filled in with paint,

“By this time | was interested in quite a lot of things from Mas Ernst, Léger, and then

to see the Americans, Johns and Rauschenberg, in some magazines. | had a girlfriend

who went to New York. who lived there and who used to get a lot of stuff sent to me,

and obviously | was incredibly impressed by Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s ways of

working.

Johns’ paintings had not yet been shown in Britain, and even in reproduction Phillips

maintains that he was aware only of the targets. Even this scanty evidence, however,

provided vivid clues to a new approach to picture-making. Most of the early criticism

of Johns’s work concentrated on his choice and use of subject matter, the way in which

a target. for instance, acted as ‘some simple visual symbol’, satisfying in a matter-of fact

way Modernist demands for fatness and anti-illusionism and encouraging the basic

act of looking. Crucial, too, was the face that the paintings not only represented

ordinary objects but took the actual form of those objects. a neat solution to the

dilemma of incorporating specific figurative references while preserving the status of

the painted canvas independent of its representational function, Having already

sensed a similar identification of subject with painted object in early Italian art,

Phillips was quick to seize on the implications of Johns’ work. ‘T was interested in

making a painting that didn’t necessarily refer directly to a subject. | was trying to

make a picture that was self-contained. This was the thing at that time, One talked

about making “objects” as opposed to “paintings”, because painting at that time was

still associated in a sense with a narration of some sort, particularly in the art schools.’

Johnsian themes, implicit in Binge in the choice of the target and in the sequential array

of images in the upper register — a device used by the American in works such as

the famous Jarger with Plaster Casts of 1955 – emerge in a more structured form in

Phillips’s Purple Flag, painted over the course of three months in the summer of 1960.

Phillips recalls that he would not have chosen the Union Jack as an image if he had

been aware of Johns’s paintings of the American flag, readily admitting, however, that

the subject occurred to him as an equivalent type of image to the target.

Rather than setting a single motif against a fat ground or simply presenting it on its

own, as Johns had done, Phillips Nag, drained of its normal colour, occupies half the

surface, with the other half filled with a range of smaller motifs: a row of targets, an

American football player painted from a photograph, a grid of coloured squares containing

an arbitrary sequence of numbers, These juxtapositions establish an alternative

time scale, a sequence of actions within a static context, a suggestion emphasized

by the presence of the figure with outstretched arm. As in Italian altarpieces, in which

panels establish a narrative complement to the starkly formalized central image,

movement is introduced within a rigidly-controlled format. This device soon became

a recurring feature of Phillips’s work, for example in the invented comic-strip se-

quence of Wal! Machine 1961 of in the striptease freeze-shots of For Men Only —

Starring MM and BB 1961, in which each image is framed by a panel of polished

wood.

‘Purple Flag took me a long time to paint, constantly changing it and honestly probably

not really knowing what | was doing. All | do know is that it was the first serious

attempt at controlling the format of the painting, flattening out the surface and

still leaving areas of illusion in, It was another way of painting and another use of imagery

that, to my knowledge at that time, was not acceptable as a way of making

paintings. From three months concentrated work on this every evening, with a lot of

little drawings and thinking on the side, | probably learned more than from five years

at an art school.”

For the first time in Phillips’s work, a number of contrasting techniques are incorporated

within a single painting, each change of pace contained within a clearly-demarcated

subdivision, The flag itself is painted in a mixture of oil paint with wax.

Other areas are painted simply in oil, sometimes polished to change the appearance

of the surface, at other times imprinted with newspaper as a means of speeding up the

drying time and of creating a matt texture. Fragments of paper are allowed to remain

on the surface, a device suggested by the work of Kitaj, whose sketchy notational style

of the time was the source also for the treatment of the figure. The cancellation mark

over the figure, a random decision which was quickly wo become an obsessive image

in Phillips’s work, provides yet another deliberate break in the logic. “I was trying to

prove to myself that, within my capabilities, there are many different ways of approaching

something which, when it’s within a relatively rigid and controlled format,

could work together.”

One Five Times! Sharp Shooter 1960, painted immediately after Purple Flag, carries further

not only the amusement arcade imagery but also the principles of conscious disruption

and of intuitive juxtapositions of images from unrelated sources: a row of targets

with actual holes punched in them, a grid of selected numbers, a diagrammatic

representation of a sleeve pistol, and what appears to be a hare, half-obscured by a

cancellation mark, muttering the curious phrase, ‘JUST THE THING FOR TAXIDERMISTS

AND BATMEN’. By this stage Phillips had begun to seek out additional

visual information to use in his paintings. Diagrams he found particularly appealing;

what they represented was more or less incidental, since their interest lay in

the fact that they were found images of inexplicable fascination in themselves. The

precision of draughtsmanship required in mechanical or scientific diagrams, placed at

the service of objects which are often obscure to the uninitiated, serves to strengthen

their enigmatic status. Phillips welcomes this ambivalence between familiarity and

impenetrability not just as a means of keeping the paintings alive, but as an equivalent

for the way one goes about one’s daily business, sometimes feeling to control, at

other times failing to comprehend the significance of objects and events with which

one is confronted.

‘There are certain periods where paintings tie up more than at others, but | don’t

think it is very important if a painting does tie up with a theme. This one obviously

is to do more with a funfair and shooting, but it’s peculiar enough to obscure it a little

bit. enough to make it interesting. [fit was just a comment on rifle ranges or something,

it would be rather dull, One just had a peculiar feeling and cried to get this into

the painting, using imagery that responded to that feeling. Certain types of fairground

activity somehow came in with this type of feeling, rather like Orson Welles

would often use a hall of mirrors of something in his movies. It’s a place of fun, but

somehow it has an undercurrent of menace the whole time. People did respond to

this. The early paintings are not always what they seem to be; this undercurrent is always

there,”

Phillips’s early paintings were worked out entirely on the canvas; it was not until late

in 1963 that he began to make preparatory drawings. Taking as his starting point a

strong formal structure, Phillips would then seek to ‘fill this structure with the correct

feeling and image and balance’, an intuitive process made all the more difficult by his

insistence that the result appear as assertive and confident as possible. This ‘juggling

of dissimilar elements until it feels right’ could be an arduous process, but the effort

was not to be visible. The unpretentious imagery afforded by games, pinball machines,

jukeboxes and the like was a convenient means of establishing the desired neutrality,

though the process of building up the painting, as the artist revealed in a catalogue

statement published in 1962, was every bit as subjective as that of the Abstract

Expressionists: ‘Some pictorial organization is essential, though the result is never preconceived

but develops during the painting process. Content is important, as is the

complexity of image and idea, relationships, format and sources. Each painting in its

break-down and build-up becomes a personal experience. | like the finished object to

exist, first and foremost as a FACT, as well as an identification of myself in an environment,

and as a contribution to that environment.’

The conflicting demands of deliberation and spontaneity occasioned a great amount

of reworking in Phillips’s early paintings, and accounts for the face chat in 1961 he

completed only five pictures, each one, however, a surprisingly authoritative statement

for an artist aged twenty-two and still a student: Wall Machine, Entertainment

Machine, Burlesque Baby Throw, War Game End For Men Only — Starring MM and BB.

Varied as they may be in terms of imagery – incorporating, as they do, monsters, cartoon

characters, movie stars, pin-ups and soldiers from the American Civil War — they

are united through their common reference to games, both in terms of structure and

in the way that they engage the spectators attention.

The central structure of Wal! Machine, for instance, is provided by the solitaire game,

into which the artist has inserted tiny images of monsters upside down. The formal

simplicity of the game format supplied a heraldic image which gave Phillips the freedom

to do whatever he wanted within it. just as the regular sequence of frames below

allowed him the luxury of creating his own comic strip fantasy.

‘| was very interested then in what I called “game formats.” A game is also that type

of thing, a big image subdivided into little pictures, and you would play this, so that

the thing became a sort of visual game where more or less anything could be acceptable.

Again this was from a highly emotional point of view. I had a lot of comic strips,

but | wasn’t self-conscious that this was anything particularly important. To me nobody

had done it, so | thought I’d just stick it in, paint a comic strip. At the time there

was nothing for me to go on. There was certainly no Roy Lichtenstein around that |

knew of, or anybody else who was doing that. | never really continued it, it was just

something that | did; it was a throwaway.’

Comic strip images feature again in War/Game, though copied in this instance from

American magazines. As Phillips himself admits, this is one of the few paintings he

has done which is in context with a particular theme, that of the American Civil War,

the centenary of which was being observed at that time. ‘lt seemed very strange to me

at the time that somebody could actually celebrate a war, particularly a very brutal war

where brother was shooting brother.’ The flippancy with which the subject was being

treated by the Americans struck him as rather sinister; in recognition of this he incorporated

sick jokes into the speech bubbles emanating from the figures.

If War/Game stands alone in its satirical intentions, it nevertheless relates closety to

Phillips’s other paintings of the time in terms of imagery and of format. The gun as a

sign of irrational violence and power, already used in One Five Times! Sharp Shooter,

reappears in the assemblage of diagrams in the lower-right of Entertainment Machine,

although the contraption in the latter incorporates a pistol and a diagram of bullet

sizes, the image as a totality is invented and, it goes without saying, inoperable, The

artist remains neutral about the question of violence, Moralistic sincerity does not enter

into it, When Goya painted The Shootings of May 3rd 1808 — a painting chosen by

Phillips as the subject of the transcription required by the College – was he simply

making a straightforward political statement, or was he not also using the drama of

that violence to his own pictorial ends?

An ever wider range of techniques is incorporated into Phillips’s work during this period.

In War/Game, for instance, black gloss household paint — first used in Wall

Machine — is smoothed down with a pumice stone and played against areas of matt

paint, waxed paint, and polished paint, The uppermost row of images is painted on

separate canvases, onto which have been glued panels of polished wood. All these diverse

elements, pieced together in a craftsman like way — one befitting the son of a carpenter

— are housed finally, within a deep box frame. The actual process of construction

thus becomes another means of composing a picture, another system to be added

to the ever-growing range of possibilities. :

Similar constructive devices are used in For Men Only — Starring MM and BB, notably

in the lower row of images encased in wooden frames. The idea for this, Phillips readily

admits, relates to the paradelles of the pre-Renaissance altarpieces he so admired,

‘but it also comes from specific feeling: something Victorian, ancient, used, and menacing

at the same time, but then with imagery that was up-to-date and underground.

How conscious that was | don’t remember,’ By this time, however it is clear that

Phillips had developed sufficient self-confidence to adapt formal characteristics of the

art of Cimabue and Giotto to a contemporary context, using the imagery, materials,

blaring colours and frantic emotions of his own time. Among the elements which he

has drawn from the pre-Renaissance are the tall vertical format organized around a

central axis, the underlying symmetry subtly broken into: the use of reversals and interplay

of positive with negative forms: the notion of serialized narrative, expressed in

the form of stark repeats: a preference for an insistent frontality and for a compartmentalization

of images: and an emphasis on the physical presence of the picture by

means of its actual construction. These are all devices to which Phillips was to continue

to refer directly at least as late as Gravy for the Navy and Four Stars of 1963, in

both of which symmetrical images of seductive women framed by star shapes are presented

like the haloed attendant angels to an early Madonna,

The imagery of For Men Only is drawn from a number of separate sources. The starting

point was the bold games-board shape in the upper half, invented by Phillips as a

suitably formal container. The collaged heads of Marilyn Monroe and Brigitte

Bardot, the two great pinups of the time, were magazine photographs that he happened

to have ‘lying around,’ rather than images which he had consciously sought

out, The stars, chosen here as another standard motif equivalent to the flag or target,

have in this initial instance a punning function, although they soon became a

favoured personal element that was used in a variety of ways. The image of the hare

was partly invented and partly suggested by a Victorian game — a subject about which

Phillips had informed himself through books – of “The Tortoise and the Hare.” The

apparently random letters contained in the circles within the hare form the message

‘She’s a doll’ followed by the name of the stripper, painted from photographs, represented

in the sequence of images below. The newspaper image imprinted in the yellow

image around the hare, taken from the pop music paper Melody Maker and bearing

the clear headline “ELVIS FOR BRITAIN’ was selected, Phillips maintains, not

for its particular message but merely because it was a journal which he used to read

regularly and which reflected his interests.

It would be possible to construct various contradictory explanations of the narrative

implied by the juxtapositions of images in the painting, So many actions and written

messages are incorporated into the picture that one feels impelled to make sense of it

in thematic terms. It must be repeated, however, that there is no single resolution, no

magic key to unlocking its meaning. In order to experience the painting fully, each

spectator must work out a logic that satisfies him or herself,

The figure with outstretched arm in For Men Only — a not so distant relation of the

similarly-engaged football player in Purple Flag — functions as a sort of stand-in for

the spectator, encouraging one to approach the painting and to take part in its games.

Just as the artist has had to make a series of decisions in producing the picture, so one

is offered constant choice, There are different surfaces and different ways of applying

paint. There are a number of ways of creating images: they can be taken ready-made

in the form of collage, invented, transcribed from photographs or diagrams, or transferred

as direct imprints into the paint from newspapers. There are different ways,

too, of getting words onto the surface, such as newspaper collage, newspaper imprints

and Letterset: in Wiel Machine, by contrast, the words are written by hand. The possibilities

are endless, limited only by the artist’s sensibility and intuition.

Each of Phillips’s paintings at this time operates according to its own set of rules.

Burlesque/Baby Throw incorporates pin-up photographs collaged onto the surface and

varnished, along with four wooden rings which, in theory, can be thrown at the canvas.

Not without irony, Phillips here takes to its literal conclusion the notion of spectator

participation implicit in Johns’s targets and the combination of real objects with

painted surface in Rauschenberg’s ‘combines’ Entertainment Machine, by contrast, is

wilfully obscure in its function, combining as it does a strange mechanical apparatus,

a piano keyboard, a cancellation mark and the head of the Amazing Colossal Man. A

collaged panel in the upper-right, bearing the words ‘Modern Schools,’ appears to

take the form of an Abstract Expressionist painting by Clifford Stull, although Phillips

denies that he was consciously making an impudent gesture towards ‘modern schools’

of painting,

Phillips maintains that the very disparateness of the imagery he was using was a motivating

force in his decision to work on a large scale. ‘] could never work on a small

scale, | never felt satisfied. | need room to move around in, and to get the compositional

elements to rotate I’ve got to have a certain amount of space in between.’

The assertiveness of Phillips’s paintings from 1961 onwards can perhaps be accounted

for also by the recognition he was already beginning to receive, as well as by his situation

at the Royal College. Phillips was president of the organizing committee of the

“Young Contemporaries’ exhibition held in February 1961, with Allen Jones, recently expelled from the College for his excessive independence, as secretary. On the advice

of Lawrence Alloway, their paintings and those of Royal College colleagues

such as Kitaj, Hockney, Boshier and Caulfield were rehung as a group shortly before

the opening of the exhibition so as to make a greater impact. The attention they

received in the press confirmed their sense of group identity, particularly as they

were under great pressure from the College staff to conform to a more traditional

way of working.

When Allen Jones was expelled at the end of his first year in the summer of 1960,

Phillips was given a provisional pass and told to reform or else leave at the end of three

months, As a matter of expediency, he painted ‘total English mannerist art school’

nudes and still-lives in grey. These pleased the staff and he was allowed to stay. At this

point he brought in the paintings reflecting his real interests, which he had been working

on simultaneously at home.

This caused, of course, serious friction with the staff and led to Phillips’s decision to

transfer in his third year to the Television School, while continuing to devote most of

his time to painting. The isolation from the staff in the end proved salutary in establishing

an independent way of working, particularly as the students themselves provided

their own standards and mutual support. | think the basic level of competition

is quite important in a very small area between people, Phillips later recalled.

“Fighting a system, and knowing that you weren’t alone, strengthened us.’

The discovery that older artists were working along similar lines was a further source

of encouragement. Peter Blake, whom he knew well by the end of 1961, if not earlier,

came closest to his way of thinking, Richard Hamilton he recalls meeting in about

1962, but Hamilton was based in Newcastle then and his paintings were not really

seen until the time of his first one-man show in 1964, Phillips knew nothing, moreover,

of the exhibition called This is Tomorrow in which Hamilton took part in 1956,

as he was aged only seventeen at the time and was living in Birmingham. Hamilton’s

involvement with the specifics of contemporary iconography, moreover, is at variance

with the more intuitive approach favoured by Phillips. A closer spirit is the Scottish

sculptor and printmaker Eduardo Paolozzi, who in Phillips’s own words is a ‘collage

assemblist’ like himself. Phillips did not meet Paolozzi, however, until 1964, and

Paolozzi’s Bunk collages of the late 1940s, often cited as early works of Pop, were not

in fact publicly exhibited until they were acquired by the Tate Gallery in 1971. It

would be wrong, likewise, to consider the discussions of the Independent Group in

the mid-1950s as a spur to Phillips, since he knew nothing of their activities.

Questions of precedence are beside the point.

Phillips readily accepts the Pop label, if it is taken in terms of attitude, style and technique

as well as of image. In a three-way interview with Allen Jones and Richard

Smith published in 1965, Phillips agreed that he was probably ‘more orthodox’ than

the others in his use of Pop imagery. „I consciously make a selection from ordinary

things which I like and then use them as a contemporary iconography. But still.” he

was quick to explain, ‘my aim is not to make comments or develop a story about the

objects | use. | try to transform them in order to make a painting and | use them simply

as images.”

In Phillips’s own estimation his greatest mentor was not a contemporary artist but an

earlier twentieth century painter, Fernand Léger. His interest in Léger began, he recalls,

while he was still at Birmingham mainly through reproductions in books, and

one of the first art books he purchased was the monograph on the artist by Robert L.

Delevoy published in 1962. In his essays on “The Machine Aesthetic, which Phillips

did not read until some years later, Léger praised the beauty of machine- made objects,

a beauty which he stressed was independent of what they represented. Feeling, not intellect,

he insisted, was the realm of painting.

The pointers provided by Léger’s work were particularly useful to Phillips because of

their flexibility. Foremost among these is the ‘law of contrasts’ — between, for example,

real and painted elements, fragments and wholes, flat and volumetric images, and

unrelated objects suspended in an arbitrary space — which Léger considered ‘the eternal

means of producing the impression of activity, of life.” Associating himself with

technology, Léger sought to create “beautiful objects’ with the aid of ‘mechanical elements,

rejecting in the process what he considered to be the overly obvious individualism

of the autographic mark.

“Léger did exactly what I do. He goes into the street and sees a photograph of the

Mona Lisa and thinks, “That’s exactly what | want with a bunch of keys.” That’s a totally

pure gut reaction. This is where | feel a certain affinity. He would go to the industrial

fairs and find the things beautiful, and | agree totally with him. But I’m not

obsessed with technology in the way that he was. because I don’t share his dream of

industrialization. In fact totally the contrary, but they still fascinate me as elements

for a painting.”

Phillips’s interest in Léger led him in to the work of Americans such as Stuart

Davis, Charies Demuth and Charles Scheeler, and linked up also with the work of the

Dadaists Kurt Schwitters, whose collages consisted of humble found objects. and

Francis Picabia, whose diagrammatic portraits of machines find echoes in works by

Phillips such as Mororpsycho/Tiger 1961/62. Equally important to Phillips as a source

of ideas was Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s pioneering book Vision in Motion, originally published

in 1947, which made a strong case for the harnessing of technology to art as a

means of expressing feelings in a manner appropriate to our age.

Technology initially entered Phillips’s work in the form of imagery, and it was only at

a later stage that he became interested in employing machines as working tools. The

double motorcycle engine in Motorpsycho/Tiger, for instance. was drawn by hand

from a diagram in a magazine. The engine’s role, in a sense, is as a substitute for the

figure. While the cyclist is represented as a helmeted head with little trace of personality,

the anatomy of the machine is lovingly detailed, treated on one side as a kind of

skeleton drawing and on the other as its exterior of metallic skin.

The sense of depersonalization in a highly industrialized society, hinted at in the subconscious

selection and placement of imagery, is implicit also in the direct use of

ready-made material in this and other paintings of 1962, The tiger head on the helmet

is a self-adhesive decal purchased at a motorcycle shop: the larger tiger head enclosed

in the green heart is a hand-painted facsimile of the same image. Similar exchanges

occur in other paintings. /Tribal | x 4 1962 incorporates four decals of a

speeding motorcycle and a schematically-painted representation of an Indian head.

While this head ts an enlargement of a decal which had been used in MotorpsycholAce

1962, the motorcycle has a later life in MULT ImotorPLICATION 1963, where it is

used both as a painted repeat and as a wooden element in relief, Similarly, the decal

which supplied the model for the leaping tiger in Motorpsycho/Club Tiger 1962 is

stuck on the middle of the painted image itself.

Since decals are an easily-accessible source of visual material, their use in the paintings

in one respect is merely a matter of convenience, an economical way of producing

an image. They exist as two-dimensional facts, and consequently can be taken exactly

as they are or merely enlarged to the required size. Phillips makes a particular

point of not changing the image so as not to ‘add’ himself to it, jealously maintaining

a neutral stance. On the other hand, they are not chosen completely arbitrarily.

I was more into the physical activities of the

city, the seedy side, than the refined side. It had a certain dynamic that I felt at home

with. The irony, however, of using something so anonymous as a personal sign was

not lost to him. ‘It’s an individualization of that machine object that somebody purchases.

and then individualizes with non-remarkable images that are already manufactured

in mass-production for individualization. So you have this contradiction in

terms.

Decals were only one of several devices that Phillips used for producing strong images

without recourse to conventional forms of drawing. In Philip Morris 1962, for instance,

three identical advertisements printed on card, which the artist had discovered

in the gutter outside his local tobacconist, supply the entire image content. The structure

for the image is provided in an equally direct way by means of a recessed canvas

at the top, a strip of hardboard to support the advertisements, and a separate canvas

divided into three equal stripes of flat colour. Two tiny canvases of the same year,

Racer and We Three Ships, propose an equally anonymous method for creating images:

in each case a single image is repeated three times with the aid of a commercially available

stencil intended for the use of children. Neither of these methods we pursued

any further by Phillips: the stencils seemed too easy a solution, while the methods

underlying Philip Morris seem to have struck him as too similar to those employed

by Peter Blake.

Pin-up imagery, which had first appeared in the form of collage in paintings such as

For Men Only and Burlesque/Baby Throw, re-entered the paintings in 1962 as readymade

self-adhesive images. In Forces Sweetheart seductive poses are struck by four

women — each one the product of the Italian illustrator Moska — stuck onto star shapes

painted with blue gloss and then varnished over. The bold chevron design, overlaid

with the outline of a heart painted with the same shiny blue, captures with great directness

the razzle-dazzle and barely suppressed excitement of big cities at night, the

contrast of reflective with matt surfaces providing a convincing equivalent to the disorientating

effect of neon lights. In Distributor similar pin-ups are stuck onto a series

of panels which can be rearranged by the spectator at will, allowing a constantly renewable

permutation of images. Once more we are invited to take part in an imaginary

game, but one involving high emotional stakes: winning bears the promise of a

seductress reclining in anticipation, while losing is signified by the presence of a coldly

aloof seated figure. The international road sign placed along the central axis provides

a vivid warning of the ‘other dangers’ which lie in wait for all those involved in

games of sexual fantasy and seduction.

Once he had used these stick-on images, Phillips soon began to seek out other girlie

images of the 1940s in magazines, transcribing them onto paintings such as Four Stars

and Gravy for the Navy, both dating from 1963. The title as well as the image of the

latter was taken from a drawing by Vargas published in Esquire. Phillips recalls that he

liked such images not because they were from the ‘40s but because they corresponded

in feeling to the other elements he had been using, neither real nor unreal.

“They complemented each other, Therefore a diagrammatic image of a motorcar was

the same as this rather diagrammatic shorthand of a woman, They were both beautiful

in one sense, and in another sense not so beautiful. There is always a certain duality.

but again my emotional reaction was positive, and | was able to make aesthetic

judgments within this particular subculture of imagery. It’s quite amazing that even

with the most awful of material one can say “This is a good decal and this is a lousy

decal,” and “This is a good pin-up and this is a rotten pin-up,” or “This is a beautiful

machine.” One is already making decisions in an aesthetic way even in the choice.’

It is often assumed that Phillips was devoted primarily to Americans, but it should be

evident by now that this was not the case. ‘I’ve never been analytical about American

things. | like American things, but I also like Japanese things, | like French things, |

like Swiss things, American cars possibly | liked more, simply because of their greater

baroqueness; they just had more interesting things to paint in them than stylized

Italian cars.’ Even the presentation of goods from a consumer’s point of view, as

Phillips points out. was not particularly an American phenomenon. “The industrial

Revolution happened in Britain, as well as advertising. The Americans maybe took it

a bit further, but there’s not much intrinsic difference. It’s been here since Victorian

times, even though it has never pushed its nose out as aggressively.

Forever Corporation is one of the few paintings that comments explicitly on American

culture, but one would be hard-pressed to interpret it as mindless celebration of

American values. The juxtaposition of one of the stars of the New York art world,

Jackson Pollock — who, incidentally, had died six years earlier — with the Statue of

Liberty on a heraldic shield, a numbered grid, two tiger heads painted from decals,

and an anonymous beauty from a German magazine, reduces the famous painter to

the status of just another motif, no more and no less important than any other. The

title of the painting, borrowed from a science fiction novel, carries its own irony.

Without stretching the point too far, it should be noted that Pollock’s head was painted

from a poster of a New York gallery exhibition, the features transferred with the aid

of a tracing and then painted in tones of grey — the symbol of free painting transformed

into a replica of a photograph.

The very wilfulness of the unrelated elements and fragments in paintings such as

Forever Corporation and Kewpte Doll 1963/64 has its logic, for it provides an equivalent

to the arbitrary manner in which one receives sensations in the course of a normal

day. Bombarded by dissimilar visual experiences which make a uniform focus impossible,

one is forced to make a selection, taking in some things and not others according

to one’s own priorities. ‘Every day things are arbitrary.’ Phillips agrees, ‘and

my sensations are arbitrary. | look at a telephone kiosk and a car passing, a girl over

there and a window up there. . . There is a logic, but it’s a logic that 1 don’t want to

define.’

Historism and factuality are closely related in Phillips’s paintings. One is constantly

forced to re-examine the evidence to confirm whether what one thinks one sees is actually

there, First glances, as one knows through experience, are often misleading, In

order to encourage us to look closer, Phillips sometimes cuts into the surface, as in

SUPinsetER and iNsuperSET, both dating from 1963, in which the star shapes and

central panels alike take the form of inset canvases. By contrast, the triangles through

which the wall can be glimpsed in Spotlight 1962/3 are not cut into the canvas, but

are the result of the piecing together of separately-coloured wooden strips. The imaginary

identification of the triangles as prisms, through which light is refracted into the

colours of the spectrum, is taken further in Gravy for the Navy by the insertion of

pieces of clear glass. On occasion motifs which appear to be cut out, like the stars in

Kewpte Doll, in fact form part of an unbroken surface, just as images which appear to

be painted are sometimes stuck on and vice versa. In MULT ImotorPLICATION the

uppermost motorcycle is in relief, literally advancing from the picture plane as a

means of matching the image of forward movement.

AutoKUSTOMotive 1964, at 2.75 x 2.75 metres the largest canvas Phillips had yet

painted, restates a number of favoured devices and concerns while introducing elements

that were to be elaborated by the artist over the following decade. As before,

there are inset panels: the star-shaped canvases are primed but unpainted, while the

inset images of carburettors are drawn in first with line and tone and then sprayed with

colour from cans, the white surrounding area painted in last. As in previous works

such as Motorpsycho/Tiger, separate panels are appended to the main canvas, though

this is now taken a stage further so that the overall shape of the canvas takes on the

form of the image represented. The twin subjects of machinery and of vehicles in motion

= both already dealt with by Phillips and with a history stretching back at least

as far as the Futurists — are represented here in a particularly aggressive form. This

work marks, too, the first overt treatment of the theme of customizing, implicit already

in the use of decals in earlier paintings such as the Motorpsycho series. Largeness

of scale, too, is brought to a logical conclusion. ‘I remember saying that | wanted to

paint a car as big as a car and a house as big as a house. | was fascinated with this idea,

but | never really took it much further. It seemed to work on that scale.’

The shaped canvas was an increasingly popular device among figurative and abstract

painters alike in both Britain and America; among the artists who had availed themselves

of it were Hockney, Boshier, Jones, Richard Smith, Frank Stella and Ellsworth

Kelly. Although he returned to a shaped enclosure in the Random Illusion series and

other paintings of 1968. Phillips did not pursue the notion for the time being and

had no urge to bring the shape out into the third dimension. He recalls chat the decision

to take the idea no further was occasioned in part by the fact that Richard

Smith had already done so in works such as Piano and Gift Wrap, but adds that ‘I was

probably more concerned with other things — with the image and the definition of

the image.”

Phillips had early made a conscious decision to use images exactly as he found them,

reasoning that whatever it was that had stimulated his imagination could operate in

a similar way for the spectator if integrated into the painting in the same form.

Photographs and decals were thus stuck directly onto the surface. By 1963, however.

Phillips had come to desire a greater flexibility in his choice of material and now felt

sufficiently confident of his technical capabilities to be able to transcribe more complicated

images by hand.

The solution he devised was to take his own photographs and then to transcribe them

to the desired scale by projecting them directly onto the canvas. SUPrasetER and

INsuperSET provide the initial instances of this ‘first mechanization’ of the artist.

Phillips took photographs of details of pinball machines and then projected them as

black and white negatives, as he later did in Kewple Doll, giving the image a mysterious

and rather sinister quality.

Rather than relying merely on what was already available, Phillips thus began at quite

an early date to add to his arsenal of images by photographing them himself. ‘I’ve

got nothing against using any tool or piece of technology that is useful, and that is

quicker than doing it some other way. To me there was no sense, when it came to

using a projector, in trying to draw something exactly how it was just by copying it,

When you want the image, you might as well photograph it and project it, then you’re

free to do with it as you want.

If you want it exactly the same, which was usually the case, it was the most convenient

way of doing it. And aesthetically rather interesting, because one can manipulate

it in scale and reverse it, which you can’t do just by thinking.

The precision with which the carburettors are depicted in AutoKUS/OMotive, and

the increased complexity with which the elements are interrelated, owe much to

Phillips’s new reliance on the projector. More or less every element in the picture was

projected, from the English Ford Consul itself to the fragment of wording in herote

perspective, Phillips’s long-standing fascination with interpenetrating spatial layers,

implicit as early as For Men Only – Starring MM and BB, now takes on a new twist

with the adaptation of 3D presentation techniques from advertisements and billboards,

While making use however, of the deliberately misleading come-ons employed

by the graphic artist, Phillips destroys his own illusions by consciously breaking

into them; the most precisely-rendered elements, the carburettors, exist only as inserts

rather than as parts of a complete mechanism, and the form of the car itself is abruptly

truncated at both ends by the demands of the canvas, construction. The space is deliberately

confusing, Every element, of course, exists only as part of a flat surface.

Customizing was an American invention, a means of individualizing cars while at the

same time suggesting their potential for speed by purely pictorial means. The appeal

to Phillips was strong, for it provided an equivalent co the artist’s own process of

painting a canvas — in the dual sense of decorating a surface and of creating illusions

— adapted to the requirements of a utilitarian object. [In AutoKUSTOMotive an essential

difference is suggested between the technology that goes into the making of

machinery and the more traditional craft skills employed in customizing through a

contrast in techniques. The equation with customizing is carried through to the materials

themselves, since both the inset panels and striped image are painted with

Kandy Kolor, a translucent automobile paint sold in cans and intended to be sprayed

on polished metallic surfaces.

One must be cautious, however, about overstating Phillips’s involvement with customizing,

for it no more explains the qualities of the mid-sixties paintings than had the

jukebox or pinball machine references in the earlier works. ‘Customizing was a peripheral

interest at the time’, as the artist himself points out, ‘but it wasn’t the aesthetic

behind the paintings specifically.’ Cars and car parts feature in each of the eight

Custom Paintings which Phillips began on his arrival in New York in September 1964

on a two-year Harkness Fellowship, but these continue to be combined with unrelated

elements; labyrinths, diagrams of nuclear power stations and of a nineteenth century

distillery, heraldic patterns from Battersea funfairs, pin-ups, and an array of dazzling

abstract patterns and geometric devices.

Although the last of the Custom Paintings was not completed until 1967, the entire series

was planned in London in 1964 in the form of precisely worked-out drawings.

‘This is the first time | started it, the first time where | made a direct logical organization

of the whole working procedure of making preparatory drawings in colour, |

felt that obviously when [ went to New York | would have a cultural shock and that!

should take something with me so that | could get immediately to work.’ He took

with him not only the drawings, but also the slides which he had used in making

them, which were protected again onto the canvases.

By 1962 Phillips had begun to eliminate the most obvious kind of handwork from his

paintings, and the anonymity of image seemed increasingly to call for a comparable

anonymity of technique. Having already begun to spray paint, the airbrush seemed an

inevitable tool; the Fellowship now gave him the financial means to buy this and other

equipment which he had been wanting to use for some time. Phillips was quoted

in 1965 as praising airbrush artists as ‘wonderful artists technically’ with a lot to offer,

adding that “Technique can be aesthetic just as much as subject or anything else.’ One

of the appeals of the instrument was that it lay outside the recognised canons of fine

art.

‘The airbrush is synonymous with certain types of imagery that one uses; it’s an instrument

that’s used in technical illustration and graphic design. | could never understand

why there was so much against it, because it really is a fascinating thing. Given

a little bit of patience, eventually | could paint very rich areas of paint.’

More than ever before, Phillips’s work now took o

the character of painted collage,

the airbrush providing a continuity of surface as seamless as that of Max Ernst’s reprocessed

collages. The homogeneity of technique neutralized the sudden ruptures of

image, making it possible, for example, for an eighteenth century diagram to coexist

with owentieth century elements.

‘| never saw any reason why anything is not valid or useful in a painting. Anything

that happens to fit with my feeling for the painting. I’m not bound by any type of limitation

other than the limitation of myself at that particular time, and that is a constantly-

changing situation. It’s not true to say that I’m concerned with high-tech imagery…

| don’t see anything wrong with taking from wherever | feel when it feels night,

and age or period makes no great difference. It’s a question of convenience, availability

and accident.”

The figure in Custom Painting No. 2 1964/65, for instance, was taken ready-made

from the atrbrush manual with which Phillips was teaching himself the technique; the

nude in No. 5 1965, by contrast, was from a pin-up magazine, drawn out with the aid

of a projected slide and then painted in an invented scheme of black and pink.

“The figure is no more important than anything else in the painting. They’re all recycled

images which have been drawn by somebody else or reworked by somebody else.

The car, too, has been retouched, and the machine parts have certainly been drawn

out totally by somebody else.’ Phillips perceives the figure as another neutral image,

of no more interest than any other clement, ‘if | was concerned with the human condition

of the figure, | would be painting totally different paintings.Th’e girls that he

uses, as he himself points out, are generally removed in time, so that they have become

pictures, not people. He selects them, it is crue, because he likes them bur this is the

case with all his motifs. “Why is it that machine and not another machine? Why is it

always an automobile part and not a gas cooker or something? Every image is chosen

by my personal preference. lt makes no difference… Each particular element in that

picture — and | call them “elements” — is a device, amongst many devices, to produce

al painting.

Phillips’s attitude is not far removed from that of Léger, who wrote in 1952 that ‘One

may consider the human figure not for its sentimental value but only for its plastic

value. That is why in the evolution of my work since 1905 unul now the human figure

has remained purposely inexpressive.’ The figures in No. 5 and in later paintings

by Phillips such as Sefect-O-Mat Rear Axle 1971 and Ant-O-Matie Cudacutie 1972 recall

Léger, too, in the way that they float arbitrarily against the painted ground.

‘Léger’s things weren’t earthbound. That’s what interested me about his as opposite to

Magritte’s. Magritte’s are always in a normal setting, apart from the very early pieces,

and even then they were always a sort of half-landscape or something, It’s interesting

that Léger avoided the connotation of the usual Surrealist thing that it was a normal

environment. It was their particular kick of putting something strange in a normal

environment. | liked it when it was ous of this.”

Phillips devised his own system for producing the Custom Paintings, a method which

he continued to elaborate until the mid-seventies. Using oil paint mixed with Magna

— a medium which curtailed the drying time and thus made respraying more convenient

— he first painted in the backgrounds. having marked off the image areas with

masking tape and tissue paper. Designs such as the moiré pattern in No. 4 1965 were

invented, sprayed in blocks with the aid of stencils cut by the artist. The more detailed

areas were then painted in with the aid of projected slides. The shiny metallic surfaces,

which provide an other wordly ground similar to that of the gold leaf on icons, were

painted with regular artist’s quality silver ot! paint.

Although the Custom Paintings were all planned before Phillips’s arrival in New York,

visualized from the start as airbrushed pictures, the artist’s experience in New York nevertheless

instilled in him a respect for professionalism and an urge to take ideas to their

final conclusion. ‘] became more and more interested in making this total commitment

to something. I think that | learned from America… | think that | took my basic ideas

and I sort of doubled up and doubled up and doubled up on just how banal and aggressive

| can get, and how clichéd | can get. and | took it to the extremes. | think to

greater extremes than most of the Americans, because I really worked with banality and

painted it banal. They can be particularly nasty, because they’re so totally uncompromising

in every way, and using absolutely contemporary imagery. Some of the images,

I think, didn’t even get to the magazines before | used them, because | took them

straight from the photographer who made the commercials… | was just very interested

in seeing if | could make something from just opening a book and taking this out.’

The notion of collaboration implicit in Phillips’s work since 1960 — in his appropriation

of techniques from commercial art as well as in his useo f found material and of

images reflecting popular taste — was reformulated in the Custom Paintings with the

suggestion that art could be tailor-made to suit the requirements of a particular owner

or of the public at large. This idea became the subject of a collaborative project on

which Phillips began work in 1965 with the English artist Gerald Laing, Laing, who

moved to New York in 1964 at the invitation of the dealer Richard Feigen and who

had met Phillips briefly in London, was approached by Phillips with the idea of working

together. Thinking at first along the lines of producing a joint painting, they decided

instead to form themselves into a market research organization, Hybrid

Enterprises, with the aim of producing an art object determined by the demands of

the informed consumer.

Phillips and Laing together constructed ewo kits, containing samples of colours, patterns,

shapes and materials — from canvas, paint, wood and fabrics through to modern

synthetic and industrial materials such as plastics and metals — and devised a questionnaire,

with the intention of feeding the results through a computerT.he 137 people

interviewed – mainly from New York, but also from London, Los Angeles,

Chicago and other cities – were all critics, collectors, and arts administrators rather

than artists. The computer was an integral part of the process, and thanks to the support

of an influential art-lover the sophisticated set-up of the Bell Telephone

Company headquarters was made available to them. Through their lack of experience

with the technology involved, they found that they had framed the questions in such

a manner that the results could scarcely be fed into the computer.

The colours, materials and dimensions were averaged mathematically, while the

shapes had to be decided upon in a more subjective manner.

‘There were contradictions. but we carried these contradictions all the way through.

We had to interpret, but the materials and everything else that was there was demanded.

It was a democratic art object. The majority vote got through… Using a

computer was more of a gestural thing than an actual necessity, The whole thing was

gestural; it was hardly a serious scientific analysis, but it was carried through to a logical

conclusion.’

Both Laing aa nd Phillips admit ftankly that the choice offered was not as free as the